A 79-year-old man with poorly controlled Parkinson’s disease was scheduled for implantation of electrodes for deep brain stimulation under mild sedation. He was right-handed, English-speaking, and oriented to time and place. His memory was good, but he had a marked tremor. Current medications included levodopa, bromocriptine, selegiline, pramipexole and amantadine, all of which had been withheld for 24 hours to allow the surgeon to recognize when he obtained maximal effect from stimulation. The patient had become very depressed recently and sertraline hydrochloride had been prescribed. Hypertension was managed with hydrochlorothiazide and amlodipine. He weighed 95 kg, with a body mass index of 37 kg/m2.

An anesthetic team, including an MD and a CRNA—both of whom were on locum assignment—was asked to manage the case. They were informed that the surgeon only wanted some monitoring with very mild sedation.

The head frame was attached under local anesthesia, and the patient was placed in a semirecumbent position. The patient was started on fentanyl 25 mcg and a very low dose dexmedetomidine infusion, 0.3 mcg per hour with nasal cannula oxygen, 2 L.

The patient appeared comfortable, and the procedure commenced with local infiltration for the Burr hole. About two hours into the case, the patient began to cough and complained of chest pain. The surgeon asked that the patient be kept still. The CRNA tried unsuccessfully to talk to the patient, who was trying to grab his chest and continued coughing. Believing the patient was experiencing a heart attack, he gave morphine-7 5 mg, placed a nitroglycerine patch and called for help.

The patient’s blood pressure was 210/110 mm Hg. He was now in atrial fibrillation at a rate of 150 beats per minute. The anesthesiologist arrived and attempted to intubate, but could not navigate the head frame. The surgeon and neurophysiologist again insisted that the patient be kept still as the case was almost finished. The CRNA again tried to pass an endotracheal tube but the capnograph showed a straight line. (A check of the machine later indicated it was not plugged in.)

The patient began to develop severe respiratory distress. The surgeon then broke scrub and prepared for an emergency tracheotomy. Once more the frame was in the field, and extensive bleeding ensued. Finally, the frame was removed and the airway secured, but not before the patient suffered cardiopulmonary arrest. He was partially resuscitated but died a few days later.

Discussion

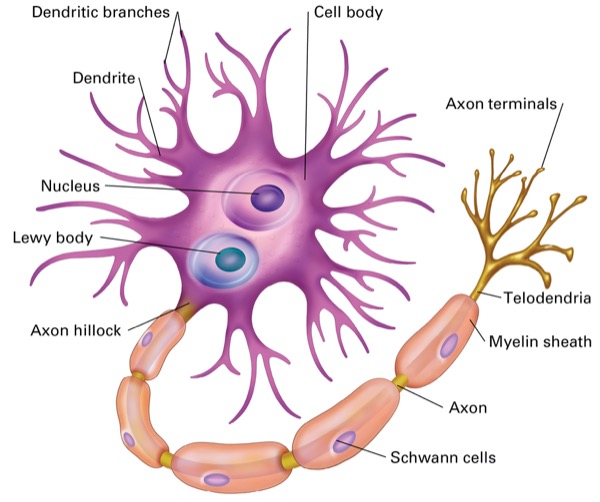

Parkinson’s disease is a degenerative disorder of the central nervous system, mainly affecting the motor system. Symptoms include tremor, rigidity, slowness of movement, and difficulty with walking. Cognitive and behavioral problems, including depression, anxiety and apathy, are common. The motor symptoms of the disease result from necrosis of cells in the substantia nigra of the midbrain, causing a deficit of dopamine. This cell death appears to involve the buildup of misfolded proteins into Lewy bodies in the neurons (Figure 1).

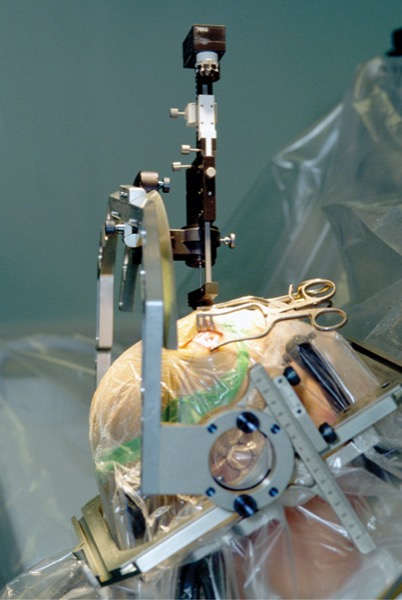

Medications that increase dopamine availability tend to become less effective over time and deep brain stimulation (DBS) may be recommended to decrease the tremor. This neurosurgical procedure involves the placement of a neurostimulator, which sends high-frequency (>100 Hz) electrical impulses, via implanted electrodes in the ventrolateral thalamus, internal pallidum and subthalamic nucleus (STN). The electrodes are implanted under local anesthesia; and usually at a later date, the stimulator (generator) is implanted in the chest wall under general anesthesia and connected to the electrode leads. The procedure is approved by the FDA as a treatment for Parkinson’s disease, since 1997.

Preanesthetic Assessment

Medication prescribed for Parkinson’s disease may cause cough, orthostatic hypotension, nausea and fatigue. Laboratory studies should include complete blood count, electrolyte panel, and renal and liver function evaluation. The anesthetic plan should be explained to the patient, as there may be several sites including radiology, the operating room and return to radiology. While the surgeon prefers that the patient be awake to allow assessment of the efficacy of the stimulation, continuous monitoring of vital signs and sedation are protocol. Aspiration is likely and prophylaxis must be provided. A dry mouth can be alleviated with ice chips. Urinary catheterization can be avoided in the awake patient by minimizing fluids and using a condom catheter. Awareness of the surgeon’s protocol regarding blood pressure management must be reviewed. Above all, the anesthetic care providers must be familiar with the head frame and know how to remove it in an emergency. All airway devices, including a supraglottic airway, must be at hand if standard intubation cannot be achieved immediately.

Anesthetic Management

Of the standard ASA monitors, perhaps the most important is the capnograph. The patient is in a sitting position and breathing spontaneously, and thus is at constant risk for entrapment of air from open venous sinuses in the bone around the Burr hole or on the surface of the brain. A sudden decrease in end-tidal carbon dioxide that may also be accompanied by tachycardia, coughing and chest pain requires that the surgeon be alerted to flood the field, and the patient be returned to the supine position. These maneuvers usually correct the situation. However, such strategies, not implemented, can cause the situation to progress to cardiac arrest as air accumulates in the alveoli, accelerated by the negative pressure of coughing and forced inspiration.

No anesthetic agent has been shown to be superior although all of them should be administered in reduced dosages. Remifentanil may increase rigidity. Benzodiazepines are not recommended. General anesthesia has been used in selected cases with good results.

Postanesthesia Care

Medications can be resumed almost immediately. There is usually little pain. In some centers, the patient is discharged the same day, although in some instances an overnight stay is preferred to ensure no bleeding or seizure activity. The patient must return for implantation of the pulse generator a few days later, an outpatient procedure that is done under general anesthesia.

Conclusion

Patients presenting for DBS are usually older with multiple comorbidities. In the sitting position with spontaneous respiration, air is easily sucked into open venous sinuses. Capnography can detect air embolism immediately.

Anesthetic care providers should ensure knowledge of function of any devices close to the airway and that all monitors are working. Communication with the surgeon and neurophysiologist is essential.

Frost is a clinical professor of anesthesiology, perioperative and pain medicine. She began her career in 1966, as a fellow in anesthesiology at Bronx Municipal Hospital, in New York City, and retired from clinical practice in 2016. She started writing a CME review series regularly for Anesthesiology News in 1980, which is now called “The Frost Series” in honor of her contribution. She has also been a member of this publication’s editorial advisory board for more than 40 years.

Frost reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Please log in to post a comment