Originally published in our sister publication, Pain Medicine News.

One of the first long-term, follow-up studies of its kind has concluded that the majority of children and adolescents treated for complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) still suffer some degree of related pain as adults. Interestingly, the study also found that with each subsequent year from CRPS diagnosis, the odds of pain in adulthood increased by 61%.

These findings, the researchers said, should help pain clinicians set realistic expectations for young CRPS patients regarding the expected trajectory of the condition.

“My colleague Becky Wong [MD] and I have taken care of many children and teenagers with CRPS through the years,” said Elliot J. Krane, MD, a professor of anesthesiology, perioperative and pain medicine at Stanford University, in California. “So, we wanted to go back and see know how these patients are doing, now that they’re grown.”

The researchers identified subjects by searching their children’s hospital’s medical records for patients whose charts were coded with CRPS type 1 or type 2 between 1994 and 2018. Those patients, now aged 18 years or older, were eligible to participate in the two-part survey.

The first part included general questions on the current state of the previously affected CRPS limb. The second part included the Short-Form 8 Health Survey (SF-8), a validated eight-question survey of health-related quality of life.

Results were reported in summary scales of Physical Component Score and Mental Component score. These scores were scaled according to a norm-based scoring system, in which each scale had a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. When a participant’s individual scale score was less than 45 or a group mean scale score was less than 47, health status was considered to be below average.

Overall, the survey had a 55% response rate, yielding a final cohort of 53 patients (mean age, 19.1 years; 77% female; mean years since CRPS treatment, 6.0).

“Of course, we were disappointed that we weren’t able to find longer term outcomes in older patients than we did,” Krane said in an interview. “Yet, it’s not surprising. Between 1994 and approximately 2005, we only had paper hospital records, so we were dealing with telephone numbers and addresses that were 25 years old, in some cases. So, the likelihood of finding those older individuals was very small. Nevertheless, I still think the information we got was useful and informative.”

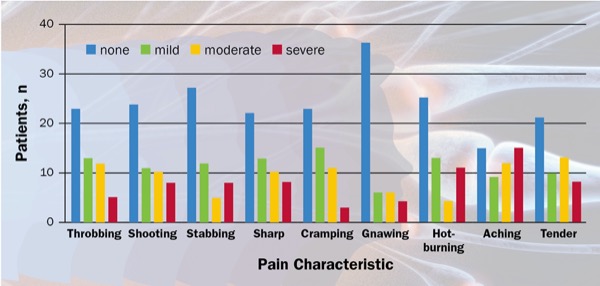

Reporting in an abstract presented to the 2020 virtual annual meeting of the International Anesthesia Research Society (abstract PAIN MEDICINE-19), Krane reported that 68% of respondents (n=36) reported some degree of pain at the time of the survey.

These findings proved surprising to the investigators. “We predicted that the majority of these patients would be doing extremely well, with no symptoms whatsoever,” Krane noted, “because that’s often how they graduate from our programs. They’re doing great and we don’t see them after that.”

In contrast, 32.1% (n=17) reported spread of symptoms beyond their original affected limb, and 37.7% (n=20) experienced recurrent symptoms that required further evaluation and treatment.

Regarding predictors of pain, no significant associations were found between patients’ reported race and occurrence of pain. Only the patient’s age at the time of CRPS diagnosis was found to be significantly associated with pain at follow-up (P<0.05).

The researchers also used logistic regression to predict patient pain according to age at CRPS diagnosis. This analysis found that each one-year increment in age at the time of diagnosis increased the odds of having some pain at the time of the survey by a factor of 1.61—an increase of 61% (P=0.0049).

Analysis of health-related quality of life revealed that the entire group had below-average SF-8 scores in both the composite physical component (44.4) and composite mental component (43.4). These scores, the researchers said, are congruent with the finding that most CRPS patients have pain in their young adult years.

Despite the findings, Krane was encouraged that the pain experienced by most patients was not life-altering. “Fortunately, most patients have symptoms that are either mild or intermittent,” he explained. “In other words, they’re quite functional.”

Given these findings, the researchers hope to offer children and adolescents with CRPS a more realistic long-term picture of their pain. “I think people deserve and need accurate prognostic information,” Krane said.

As David D. Sherry, MD, discussed, the study demonstrates the need for more long-term outcome studies in children with CRPS, especially with the varying presentation of CRPS. “Some of these patients call me with pain when they’re 35 years old, and my first question is always, ‘What else is going on in your life?’” he said. “Because there’s a psychopathophysiology to CRPS that is difficult to measure.

“So, I think outcome studies need to be more robust in terms of all the different manifestations that these children are prone to,” added Sherry, the director of the Amplified Pain Program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “It’s probably going to take a country like Sweden or Denmark, where they can track people throughout their lifetimes, to see how these things play out in the long term.”

—Michael Vlessides

Krane and Sherry reported no relevant financial disclosures.