University of Chicago Medicine

Amid the pandemic, civil unrest and claims of police brutality, matters concerning race, class and bias are leading the news headlines and are on most of our minds. As with any service sector job in which we protect and serve our most vulnerable people at their most vulnerable times, the practice of medicine is about personal connections and human experiences. Yet the practice of medicine is not immune to prejudice. Now more than ever we must understand our shortcomings, address our failures, and find a better way to care for our patients and our society.

The Growing Underrepresentation in Medicine

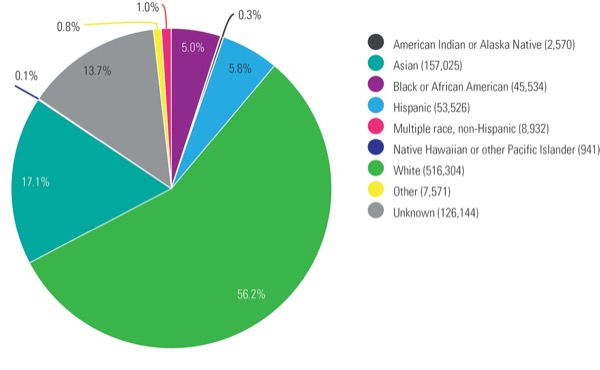

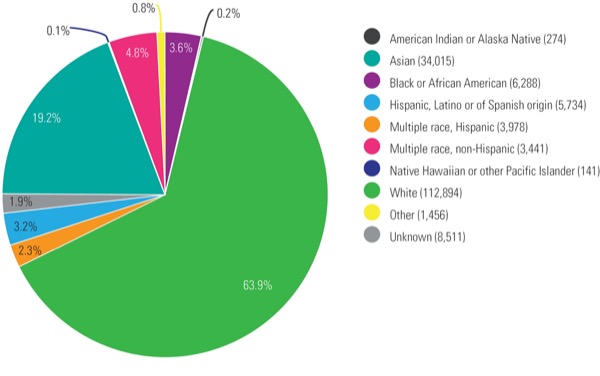

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) defines underrepresentation in medicine as “racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population.” These populations include Blacks/African Americans, Latinos, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders. Despite attempts to moderate disparities in our profession, these issues are still present and may be worsening. For example, in the United States, non-Hispanic whites make up 56% of the population and constitute 64% of all physicians, including 62% of anesthesiologists and 51% of pain medicine specialists (Figure 1). By comparison, Blacks and Latinos make up 31% of the population and constitute just 11% of all physicians, including 10% of anesthesiologists and 12% of pain medicine specialists (Figure 1). The disparity in underrepresentation is higher in academia, as Blacks and Latinos combined make up roughly 6% of full-time academic physicians compared with 83% of their non-Hispanic white and Asian counterparts (Figure 2).1

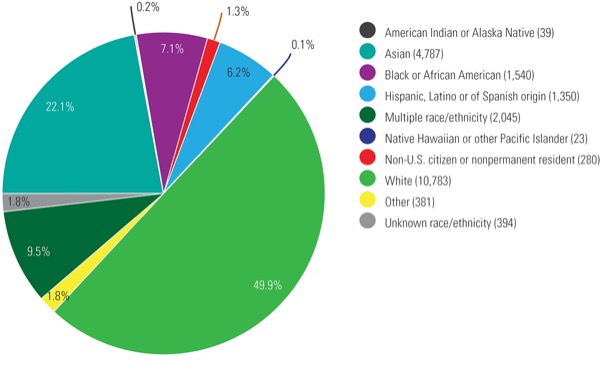

Demographics in the United States are shifting. Yet, while less than 50% of the population will be non-Hispanic white by 2045, the percentage of underrepresented minorities (URMs) is expected to remain a small fraction of U.S. physicians.2 Consider the current physician pipeline. Based on medical school data aggregated by the AAMC for the 2018-2019 academic year, roughly 15% of medical school applicants were Black or Latino, with only 13% matriculated and 11.5% graduating from medical school (Figure 3). The reasons for this deteriorating—indeed broken—pipeline are multifactorial, including a higher average burden of premedical educational debt among URMs, abolishment of policies such as affirmative action, limited resources and fewer mentors for URM students.

Why We Need URMs in Medicine

The United States is diversifying. In medicine, this diversification has led to improved patient satisfaction, better health care delivery and increased financial performance.3,4 Our patients benefit when they are cared for by a diverse workforce, which is why initiatives that facilitate diversification through recruiting, retaining and developing URMs in medicine are essential. Racially diverse hospitals tend to drive down major complications and even death among minority patients. This, in part, is attributed to higher cultural proficiencies among clinicians.5 Clinicians who are familiar with the life experiences of their patients are often better equipped to understand their core values and the social and cultural circumstances that influence their health care decisions. The quality of health care is heavily influenced by the intimate interactions between doctors and patients. For example, we know that Black men who are patients of Black doctors are more likely to opt in for testing, including diabetes screenings and cholesterol monitoring. According to Alsan et al, there is a certain comfort level and trust that occurs when core values are shared.6 There is no more jarring example of this than a recent study that found the mortality rate of Black babies is reduced by about half when they are delivered by Black physicians.7

{RELATED-HORIZONTAL}The need for understanding and empathy among hospital staff and clinicians is particularly important in pain management. In the United States, for example, the experience and treatment of pain is highly variable, often dependent on a patient’s race, ethnic group, native language and socioeconomic status.8 For example, Black patients are less likely to receive appropriate pain medication and often are not administered pain medication compared with their non-Hispanic white counterparts.9

Unfortunately, these trends will likely persist and reinforce the need to not only address gaps in research, funding, cultural education and training, but also to diversify the workforce to complement a diverse patient population.8,9

Increasing URMs in Medicine

Creating a diverse and inclusive workforce is best accomplished via well-planned, intentional decisions to increase the number of URMs at the institutional level. Such decisions require commitments and investments from leaders who are responsible for hiring, mentoring and creating long-term career opportunities.

A good starting point is to invest financial resources in recruiting, retaining and developing high-caliber talent. Many leading institutions are devoting time and money to diversity and inclusion training. For example, Columbia University is investing more than $100 million in a five-year program to increase the diversity of its faculty. Such programs not only help boost recruiting and retainment but also set a tone that prioritizes a culture of diversity and inclusion.

Building a diverse and inclusive workforce often begins with data collection on race and ethnicity within the organization. Data collection will quickly highlight gaps and disparities in an organization’s diversity performance—information that can be used to develop specific plans to address inequities.

This approach has been used successfully by both the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA). Indeed, the ASA credits its robust data collection for recognizing that gender and minority gaps existed within its leadership positions and providing a more granular, deeper understanding of where discrepancies could be rebalanced.10,11 The findings ultimately led to interventions that specifically addressed gender disparities within the organization.

ASRA dedicated 2020 to recognizing the impact and achievements of women in regional anesthesia and pain medicine. The organization is eliminating male-only panels at national meetings, acknowledging women for outstanding contributions to regional anesthesia and pain medicine, and ensuring women have key roles on national committees.12

Research and hands-on data collection also provide a better understanding of less obvious aspects of an organization, such as when URMs and women are in leadership positions, it influences the kinds of trainees a program attracts. For example, when pain medicine fellowships are led by female program directors, these fellowships are more likely to train female pain fellows.13 Clearly, a commitment to diversity and inclusion among those responsible for choosing leadership roles ultimately influences the composition of the workforce, its values and the tone of the organization.

Walk in Another’s Shoes

A medical workforce that reflects the diversity of our communities will be better prepared to meet the needs of all patients at their most vulnerable moments. Until such a workforce is a mainstay of our profession, we must continually fine-tune our diversity efforts, and do so despite external forces that continually seek to divide and polarize. Now more than ever we must redouble our efforts to find commonality while appreciating our differences in perspectives, cultures, beliefs and social strata—none of which requires similar skin colors or experiences. We must be open to change, to listening to alternative opinions, and to engaging in meaningful dialogue. When our only dialogue is with people who share our beliefs and backgrounds, we not only lose the ability to walk in another’s shoes but also unwittingly perpetuate underrepresentation, racism, sexism and injustice.

The author reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Editor’s note: As with all Commentaries, the views expressed in this piece belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the publication.

References

- US Census Bureau. Published June 29, 2020. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://data.census.gov/ cedsci/ profile?q=United%20States&g=0100000US

- Vespa J, Medina L, Armstrong D. Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060. US Census Bureau; 2020:15. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://www.census.gov/ content/ dam/ Census/ library/ publications/ 2020/ demo/ p25-1144.pdf

- Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, et al. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997-1004. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.9.997

- Gomez LE, Bernet P. Diversity improves performance and outcomes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111(4):383-392. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2019.01.006

- Okafor PN, Stobaugh DJ, van Ryn M, et al. African Americans have better outcomes for five common gastrointestinal diagnoses in hospitals with more racially diverse patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(5):649-657. doi:10.1038/ajg.2016.64

- Alsan M, Garrick O, Graziani G. Does diversity matter for health? Experimental evidence from Oakland. Am Econ Rev. 2019;109(12):4071-4111. doi:10.1257/aer.20181446

- Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117[35]:21194-21200.

- Meghani SH, Byun E, Gallagher RM. Time to take stock: a meta-analysis and systematic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Med. 2012;13(2):150-174. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01310.x

- Meghani SH, Polomano RC, Tait RC, et al. Advancing a national agenda to eliminate disparities in pain care: directions for health policy, education, practice, and research. Pain Med. 2012;13(1):5-28. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01289.x

- Wong CA, Stock MC. The status of women in academic anesthesiology: a progress report. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(1):178-184. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e318172fb5f

- Toledo P, Duce L, Adams J, et al. Diversity in the American Society of Anesthesiologists Leadership. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(5):1611-1616. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001837

- Viscusi E. President’s message: inclusivity, diversity, and ASRA’s celebration of the year of women in ASRA. American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Newsletter. Published November 2019. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://www.asra.com/ asra-news/ article/ 211/ president-message-inclusivity-diversity

- Hagedorn JM, Moeschler S, Goree J, et al. Diversity and inclusion in pain medicine. Reg Anesth Pain Med. [Epub Jan 21, 2020]. doi:10.1136/rapm-2020-101284