Former Vice President for Medical Affairs, Carilion Medical Center

Partner, Anesthesiology Consultants of Virginia Inc.

Roanoke

Carilion Clinic is a nonprofit academic health care organization serving nearly 1 million patients in Southwest Virginia. Its flagship, Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital, is an 850-bed, tertiary referral center providing Level I trauma care. As such, it gets its fair share of difficult airways: trauma, angioedema, morbid obesity, head and neck cancer, facial trauma, etc.

As in many large academic institutions, airway management is performed by several specialties with varying levels of expertise in difficult airway management. An airway alert process was developed to navigate the complexity of managing a patient in acute respiratory distress who potentially requires an emergent/urgent surgical airway. Modeled after the code blue protocol, the airway alert is designed to quickly bring expert personnel and resources to patients with difficult airways and facilitates safe and efficient care.

As a member of the Society for Airway Management, I became aware of other institutions that had established an airway alert or code airway process and realized that our patients would also benefit. Consultation with other society members provided a wealth of information. Development of an airway alert involves buy-in and collaboration across multiple specialties, and our first step was to establish a multidisciplinary Airway Committee. This committee met monthly for approximately 18 months.

I was the vice president for medical affairs when I initiated the project, so I represented the hospital’s administration; other participants represented anesthesiology, emergency medicine (EM), ENT (ear, nose and throat) surgery, critical care medicine, trauma surgery, nursing, respiratory therapy and—thankfully—a performance improvement process engineer. Involving all stakeholders is important so each can fully participate and have their concerns addressed and met. For example, the EM physicians raised concerns that the anesthesiologists would “swoop in” to manage these difficult airways and disallow participation by the EM residents. In response, the anesthesiologists agreed to involve the EM residents when possible, considering their clinical acuity. The EM residents were also welcomed to follow the patients to the OR if a surgical airway was deemed necessary.

Another concern was the disposition of patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) and brought to the OR for a surgical airway. A process was established for direct admission from the OR to the ICU by critical care medicine, otherwise these patients would either return intubated to the ED or remain in the PACU.

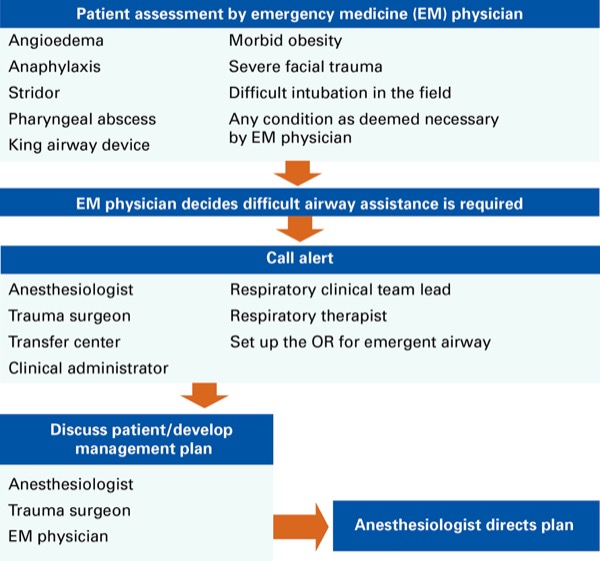

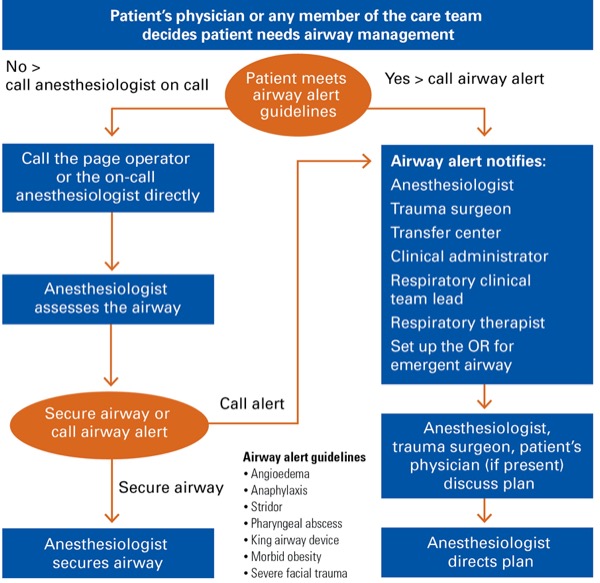

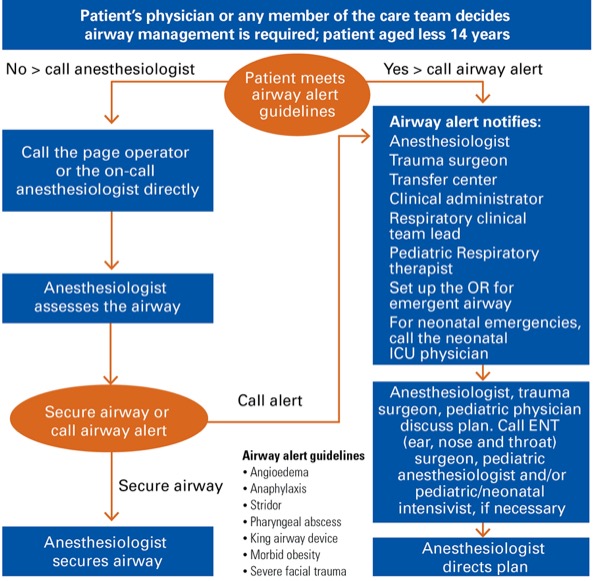

The committee’s work focused on developing criteria by which patients would be directed toward the airway alert process. Pathways of care were discussed for patients presenting to the ED and for inpatients. Pediatric intensivists were consulted in mapping out a process for pediatric patients. Our performance improvement engineer mapped out multiple pathways for patient management before we decided on the pathways shown (Figures 1-3). It was also important to standardize airway equipment and carts that would be brought to a patient’s bedside during an alert. Another important aspect of the committee’s work was education. It was important to ensure that physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists throughout the hospital became aware of the alert and when to call an airway alert instead of calling only the anesthesiologist, as they might do for a routine intubation.

When an airway alert is called, those paged to the patient’s location are the anesthesiologist, trauma surgeon, nursing clinical administrator, respiratory clinical team leader and respiratory therapist. The OR is also notified so that a room can be set up quickly for a surgical airway. The difficult airway cart is brought by the respiratory therapist, and everyone called converges at the patient’s bedside to assess their condition.

The fundamental question for the physicians who are present is whether the patient’s airway can be safely managed at the bedside or better managed in the OR. If a surgical airway seems likely, will the trauma surgeon be in attendance or is there time to call the ENT surgeon? ENT surgeons do not take in-house call and have a 30-minute response time. For pediatric patients, a similar concern is that the pediatric anesthesiologist on call also takes call from home with a similar response time.

Incidents involving emergent management of the difficult airway are relatively low volume, yet very high risk. As such, near perfect execution is required to achieve an optimal outcome. The airway alert process provides a multidisciplinary rapid response team for skilled airway management, thus improving patient safety through collaboration.