SAN FRANCISCO—As the environmental burden of healthcare becomes more widely understood, researchers are working to figure out how their care contributes to phenomena such as global warming and what, if anything, can be done to mitigate these effects.

This question was the focus of a debate held at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists.

“Healthcare emissions are a big problem and the world is recognizing it,” commented moderator Seema Gandhi, MD, a clinical professor in the Department of Anesthesia and Clinical Care at the University of California, San Francisco. “We are no longer going to accept it as collateral damage for providing the care we give. We cannot continue our current way of practice and hoping that our drugs and resources will last forever.”

Starting With Anesthetic Gases

For Rachel E. Outterson, MD, a clinical assistant professor of anesthesiology, perioperative and pain medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine, in California, addressing the use of regional anesthesia is a good place to begin.

“I will start with the low-hanging fruit,” Outterson told Anesthesiology News. “All of the anesthetic gases we currently use are potent greenhouse gases. We give these gases to our patients; they breathe them in and metabolize very little.”

Most of the gases that are used during surgical procedures, Outterson added, are routed into scavenging systems, which move them away from the OR before releasing them into the atmosphere.

“They are not processed, not captured; they just go out into the environment where they will continue to exist for several years,” she said.

The resulting waste, and its corresponding effect on the planet, is substantial.

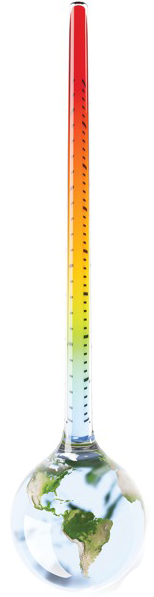

“We describe how potent a greenhouse gas is using a metric called the GWP, or Global Warming Potential,” Outterson said.

The GWP categorizes the heat-trapping capacity of a particular gas. As an example, desflurane—commonly known as the most polluting anesthetic gas—has a GWP of 3,714 times that of carbon dioxide of the same mass.

Indeed, gas waste during surgical procedures can be huge, with greenhouse gas emissions making up 50% of the total emissions of an entire surgery—including all the supplies, raw materials and electricity use necessary for a procedure.

“It only makes sense for us to think, ‘If we can perform anesthesia without these gases, could we probably have a much lower footprint?’” Outterson pointed out.

She highlighted a study by researchers at the Hospital for Special Surgery, in New York City, which attempted to answer this question (Reg Anesth Pain Med 2020;45[9]:744-745).

In their study, the team sought to quantify the environmental impact of using less volatile inhalational agents during regional anesthesia.

They calculated that avoiding the use of a hypothetical general anesthetic consisting of desflurane and nitrous oxide would save an amount of greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to driving 60,500 miles, or 22 back-and-forth trips from New York to San Francisco.

Since being published, however, the paper has provoked comments from many individuals who felt the team’s calculations were off.

To address this, Outterson made a calculation of her own and reached a far more staggering result. By her estimate, avoiding the use of this hypothetical anesthetic approach would save an equivalent of 8.2 million miles driven in a car, or 2,827 cross-country trips.

More Practical Solutions?

According to Galaxy Li, MD, a pediatric anesthesiologist and pain medicine physician at Nemours Children’s Health and Mayo Clinic in Florida, Jacksonville, controversy over the findings of the paper still exists, and the findings likely overinflated the impact of realistic decreases in anesthetic gas use.

“This daring discourse was criticized in follow-up with a letter to the editor because the figures used were desflurane and nitrous oxide at 2 L per minute fresh gas flow,” he said. “We all know we can safely proceed with 0.5 L per minute given that we no longer use CO2 [carbon dioxide] absorbers that create Compound A.” He also noted that there are no human case reports of sevoflurane-associated nephrotoxicity related to Compound A.

Li expressed an issue with data focused on the CO2 equivalence associated with the use of desflurane, a poor choice due to its environmental impact and, as such, is not as widely used as it once was. He also added that there are plenty of surgical cases for which regional anesthesia doesn’t apply, such as endoscopies, myringotomies and bronchoscopies. Additionally, he said specific situations like patients who are anticoagulated or who refuse regional anesthesia will require general anesthesia.

Because of these and other factors, “general anesthesia is the most versatile option here,” Li said.

“Truthfully,” he continued, “not all general anesthesia is bad—it is possible to recollect, destroy or even reuse some of these anesthetic gases.”

Yet the ideal approach, according to Li, is instead of investing in more equipment to get rid of these gases, simply to cut down on their use.

“If you think about it, elimination of these gases is really best accomplished by just not using them.”

Li cited a life-cycle assessment of greenhouse gases used in anesthesia that determined desflurane had a greenhouse gas impact 15 times that of isoflurane and 20 times that of sevoflurane on a per minimum alveolar concentration (MAC)-hour basis when administered in an oxygen/air admixture (Anesth Analg 2012;114[5]:1086-1090). He added that much waste comes from other stages of the healthcare process, not just from use during surgery.

Much of nitrous oxide gets released into the atmosphere not during procedures themselves, but during the process of refilling canisters. Suppliers often release remaining gas left in tanks before refiling them.

“Remember there is a carbon cost associated with manufacturing our products and our associated equipment, including delivery,” Li said. “When it comes to inhalation of anesthetics, these greenhouse gas impacts are dominated by uncontrolled emissions of waste anesthesia gases.”

Li also noted that the use of propofol is often far more effective and has a significantly smaller environmental impact.

“The greenhouse gas impact of propofol is nearly four orders of magnitude less than that of desflurane or nitrous oxide and primarily stems from electricity use [powering the infusion pump]. In addition to eliminating desflurane and nitrous oxide, consider total intravenous anesthesia. From a global gas perspective, propofol is the best option, but its use is not without risks to our environment.”

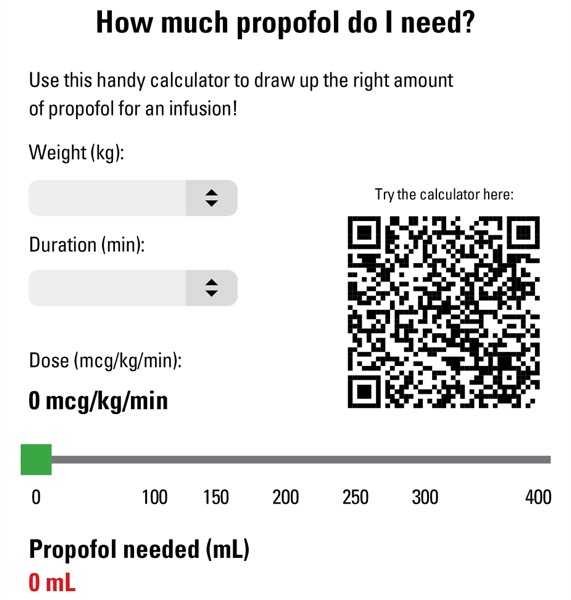

Li stressed that preparing medications after patient evaluations is key to ensure that dosages are correct and waste is minimized, especially as cases occasionally are canceled or moved into another location or time.

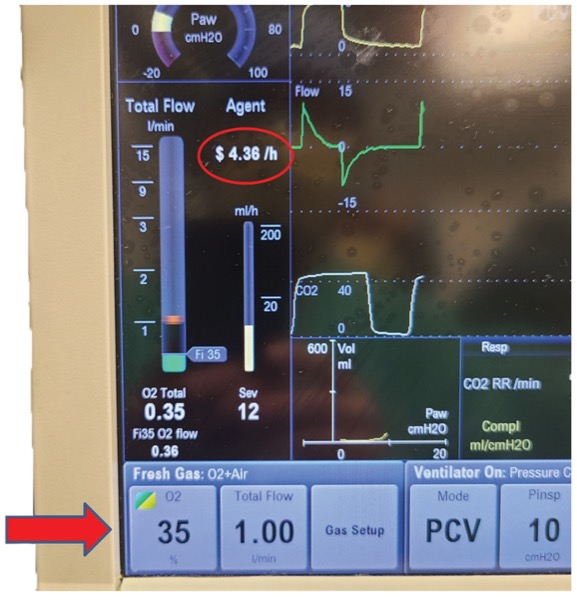

“Please, please prepare your medications after evaluating your patients,” he advised, sharing an online propofol calculator (Figure 1). Now technology can also assist in reducing anesthetic usage and saving money (Figure 2).

Many current anesthesia machines feature built-in tools that include reminders intended to help anesthesiologists adjust fresh gas flow rates, thus leading to cost savings and decreased gas use.

Despite their occasionally contrasting views on how to address the issue, both Outterson and Li stressed the importance of evaluating anesthesiology care to address the impact it has on the environment.

By Ethan Covey

Li and Outterson reported no relevant financial disclosures.