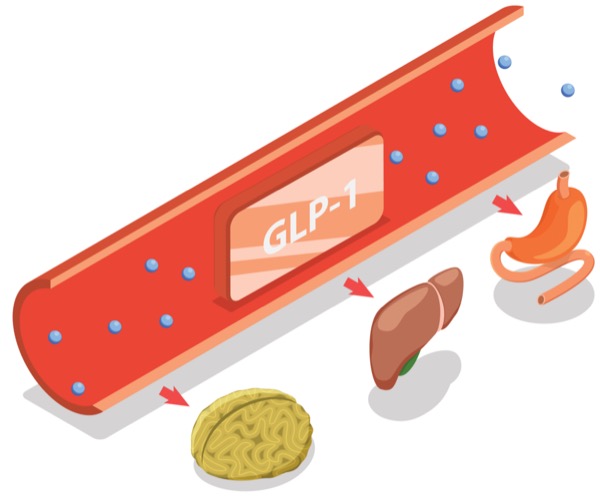

SAVANNAH, Ga.—As more Americans are prescribed glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist drugs, concerns are rising about how to best manage associated adverse gastrointestinal effects, such as delayed gastric emptying, that may increase the risk for regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents during general anesthesia and deep sedation.

In an effort to address these concerns, the ASA released consensus-based guidance on the preoperative management of patients taking GLP-1 agonists (www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2023/06/american-society-of-anesthesiologists-consensus-based-guidance-on-preoperative).

During the 2024 annual meeting of the Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia, a debate session considered whether the ASA guidance effectively addresses these concerns.

A Solid Start

Arguing the position that the ASA guidance effectively addresses concerns was Girish P. Joshi, MD, MBBS, a professor of anesthesiology and pain management at The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, in Dallas.

Since June 2020, the use of GLP-1 agonists for patients has risen by over 200% among internal medicine and endocrinologist/diabetes specialists, and by almost 500% among other medical providers (based on IQVIA LAAD pharmacy claims; U.S. Market Access Strategy Consulting).

Much of this growth has been in the drugs being used for weight loss. However, Joshi noted that they have been shown to have other potential uses, including for infertility, decreased inflammation and certain psychiatric uses.

Beyond that, he explained that many patients now get GLP-1 agonists compounded from pharmacies, meaning their use may not be accurately represented in a patient’s medical record. Patients also may not mention that they are taking these medications, thus complicating preoperative planning.

“The most important message I want to give is to ask the patient if they are on these drugs,” Joshi said. “We have to ask and emphasize that there is a concern. This shared decision making is very important.”

Regarding delayed gastric emptying, Joshi noted that “there is an enormous amount of evidence that this is a real concern, and once aspiration occurs, the consequences can be significant.”

Current Approaches by Clinicians

This begins with avoidance of elective surgical procedures during the GLP-1 agonist escalation phase, Joshi said, which typically lasts between 16 and 20 weeks. “This is the time when [patients] have significant GI issues and the possibility of delayed gastric emptying.”

Withholding the GLP-1 agonists can also be beneficial, but controversy remains as to how long.

“Some say five half-lives because that’s how long the drug takes to be completely eliminated,” Joshi said. “But do we really need to eliminate the drug completely? We just need to decrease the concentration such that the delayed gastric emptying is decreased.”

According to Joshi, this is why the ASA guidance recommends withholding GLP-1 agonists for one week before the procedure for patients who are on weekly dosing schedules.

Prolonged fasting may be another usable technique, but additional study is required to determine its benefit. Patients at risk can be identified by performing a gastric ultrasound, if possible, and those with significant GI risk should be screened.

Finally, the best approach, according to Joshi, is rapid sequence induction (RSI). However, he noted that RSI is not necessarily safe because regurgitation cannot be completely prevented. Delaying the procedure should be a last resort due to potential patient dissatisfaction.

While many questions remain, the ASA guidance shows that the organization acted with urgency to address this issue.

“The primary aim was to educate, and the secondary aim was to mitigate this problem of regurgitation,” Joshi said. “We have to address this by using a multipronged approach to improve patient safety.”

Guidance Called ‘Not Appropriate’

According to BobbieJean Sweitzer, MD, the systems director of preoperative medicine at Inova Health, in Falls Church, Va., and a professor of medical education at the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville, the ASA statement is problematic due to both its suggestion to withhold GLP-1 agonists and its recommendation to follow current ASA fasting guidelines.

“I believe these are the two things that make this guideline not appropriate,” she said.

A key concern is the duration of elimination of these drugs.

“Sometimes this is context dependent, and I think Dr. Joshi is right that we don’t know exactly how long it takes for the delayed gastric emptying effects of these drugs to last,” Sweitzer said. “It may be quite a long time and is unpredictable in any given patient.”

A study she referenced showed that one GLP-1 agonist—liraglutide—resulted in a persistent delay in gastric emptying of solids for 16 weeks (Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2[12]:890-899). A second study found nearly no change in drug concentration in the body over a one-week period (JAMA Surg 2024;159[6]:660-667).

Regarding fasting, Sweitzer pointed to a third study that concluded that fasting durations suggested by current guidelines may be inadequate in some patients (JAMA Surg 2024;159[6]:660-667).

Complicating the issue further, she said, determining how long to withhold GLP-1 medications can be quite different depending on whether the patient is taking them for weight loss or diabetes.

“The first thing we should do is make sure these patients change their fasting,” she said. “We know that fasting before anesthesia decreases the risk of aspiration, and we know from other studies that changing their diet ahead of time can significantly impact gastric emptying.”

Sweitzer recommended that if medications are to be held, it is better to do so for at least three weeks in weight-loss patients, and—when possible—for a similar period in diabetic patients. Patients who are unable to hold their medications or have symptoms compatible with delayed gastric emptying should go on a reduced-fat, reduced-fiber diet 72 hours before surgery, a full liquid diet 48 hours before surgery and a clear liquid diet 24 hours before surgery.

“This is just good for their underlying conditions,” Sweitzer said. “Diabetics should be reducing their calories, especially type 2s, and weight-loss patients will lose weight while they are off their GLP-1 agonists.”

By Ethan Covey

Joshi reported a consultantship to Merck Sharp & Dohme. Sweitzer receives funding from the International Anesthesia Research Society; is an author of UpToDate “Preoperative Evaluation” and receives compensation; is the executive editor of A&A Practice; is on the editorial staff of Anesthesiology and Anesthesia and Analgesia; and has received funding from Medtronic. She is member of the Anesthesiology News editorial advisory board.