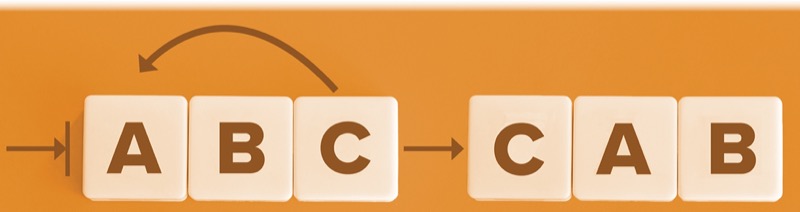

A change from Airway, Breathing and Circulation (ABC) to Circulation, Airway, Breathing (CAB) is emerging as a prominent approach in trauma care in recent years, as the gold standard.

“Someone who’s in hemorrhagic shock or bleeding, their blood pressure is typically low or can be low. When you provide intubation medications, they typically get worse and they can arrest—their pressure can drop even more,” said Jason Sperry, MD, a professor of surgery and critical care at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC).

In this patient population, it might be optimal to intubate in the OR after the patient receives a blood transfusion to give them a little more time to resuscitate first.

To further explore this novel approach, Sperry and his colleagues conducted a post hoc analysis, which they presented at the 2025 Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Annual Scientific Assembly (quick shot 5).

The investigators analyzed the results of a prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study in adults at risk for massive transfusion (ABC score >2) who required blood products and hemorrhage control surgery within 60 minutes of hospital arrival. The primary outcome was early mortality.

The study included 566 patients, with 19% receiving intubation in the emergency department (ED). Patients in the ED intubation group were more likely to have blunt trauma with shock and traumatic brain injury. These patients also required more transfusions and had longer delays in arrival to the OR.

At every time point, mortality was higher in the ED intubation group. The investigators controlled for various confounding variables, including age, sex, penetrating trauma, injury, time to OR, labs and mortality. They found that ED intubation independently predicted mortality at four, 12 and 24 hours, with increased mortality risks of 326%, 373% and 420%, respectively.

The team concluded that ED intubation is associated with higher early mortality in trauma patients at risk for massive transfusion requiring hemorrhage control surgery. This finding suggests that there may be a critical window when intubation is safer if performed in the OR.

“Shifting the focus from airway to circulation first, with an emphasis on expedient hemorrhage control and simultaneous airway management, may improve outcomes in these patients,” Sperry noted.

Putting the findings into context, he said: “You can tip the patient over the edge, and then you don’t get a shot at getting them off the OR table. You don’t get to the OR because they arrest. So, CAB is sort of the new approach. It’s always been like the airway is most important, but you have to resuscitate before you just go to direct intubation.”

Sperry acknowledged that several factors influence the decision where to intubate, such as transit time to the OR and the types of intubation drugs used—some of which have less of an effect on hemodynamics and cause less pressure drop.

In an interview with Anesthesiology News, Joshua B. Brown, MD, an assistant professor of critical care medicine at UPMC, further expounded on the dangers of coding in the ED.

“If they arrest in the ED, you really have limited options; but in the OR, you have more hemorrhage control maneuvers and can intervene in the abdomen or other body cavity if that is what they ultimately need. I’ve found that the loss of skeletal muscle tone from the paralytic can really drop preload and lead to a lot of the cardiovascular collapse, so even if using other sedation agents that should not precipitate hypotension, the risk is still there.”

One limitation of this study is its observational nature. It would be unethical to randomize critically ill patients with urgent airway needs to receive either OR or ED intubation, Brown noted.

By Naveed Saleh, MD

Brown and Sperry reported no relevant financial disclosures.