Cedars-Sinai Health System

Los Angeles

Introduction: The Advent of Trauma Teams

Since World War I, trauma healthcare delivery systems have evolved to guarantee timely care for acutely injured patients. World War I marked the appearance of forward-assisting infirmary units stationed within battle zones to allow early access to pain medication, prompt hemorrhage control and early immobilization of fractures.1 Survivors were transferred from the battlefield to distinct hospitals for definitive surgical care. Treatments, resource allocation and mobilization further improved during World War II, the Vietnam War, and the subsequent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. With modifications in treatment models, it became apparent that the support of a complementary trauma team working beside trauma surgeons became indispensable.

Preventable deaths from trauma in civilian settings were similarly frequent in the first half of the 20th century.2 As in the military, civilian trauma systems were developed to bring together several specialized trauma services and hospitals, thereby facilitating the transport of injured patients to trauma centers.3 The goal of establishing civilian trauma teams was to ensure early mobilization of more experienced multidisciplinary trauma specialists to provide targeted care under pressure. This was emphasized by Congress in the Emergency Medical Services Systems Act of 1973.4 It is generally accepted that early mobilization and trauma system development helped improve patient outcomes, but the composition of trauma teams and related communication issues varies depending on the country, hospital culture and available urgent resources.5

R. Adams Cowley, MD, was the first to describe the importance of diverse specialties in trauma teams as being fundamental to improve morbidity and outcomes.3,6,7 Petrie et al demonstrated that patients with severe trauma had significantly better outcomes when a multidisciplinary trauma team was involved compared with non–trauma-trained physicians.8 Outside the United States, an anesthesiologist is consistently present to safely manage the airway of trauma patients and assist with resuscitation, often in a prehospital environment (Figures 1 and 2). However, this role also can safely be filled by an intensivist, surgeon or emergency department (ED) physician, with an anesthesiologist on standby when initial airway management attempts fail.9 Remarkably, the R. Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center, the only stand-alone trauma center in the United States, remains one of the only centers that consistently uses anesthesia in the early stages of trauma resuscitation. Unfortunately, this practice model has not spread to other major trauma centers.

The following review discusses the history of trauma teams, the composition of international and national trauma teams, and current efforts to incorporate anesthesia into the trauma team.

International Trauma Teams And Trauma Team Leaders

In the past, early assessment of all trauma patients by a trauma surgeon was mandatory, but advances in ultrasonography and CT have reduced the need for acute surgical intervention. Only 10% of blunt injuries and 15% to 30% of penetrating injuries require going to the OR, and tube thoracostomy can resolve almost 90% of thoracic injuries.10 In the United States, anesthesiologists provide resuscitation from the OR and embolization suite to the CT unit and ICU, where the trauma patients are often ultimately extubated under anesthesia guidance. However, along with the reduction of patients proceeding to the OR, anesthesia involvement in the ED has decreased significantly.11 Anesthesia, in general, has not reliably formed acute care teams or dedicated staff groups to work with the trauma service in many hospitals, although it continues to manage all other emergent airways, including the responsibility of COVID-19 airway management during the pandemic in most major tertiary care centers in the United States, including the ED.

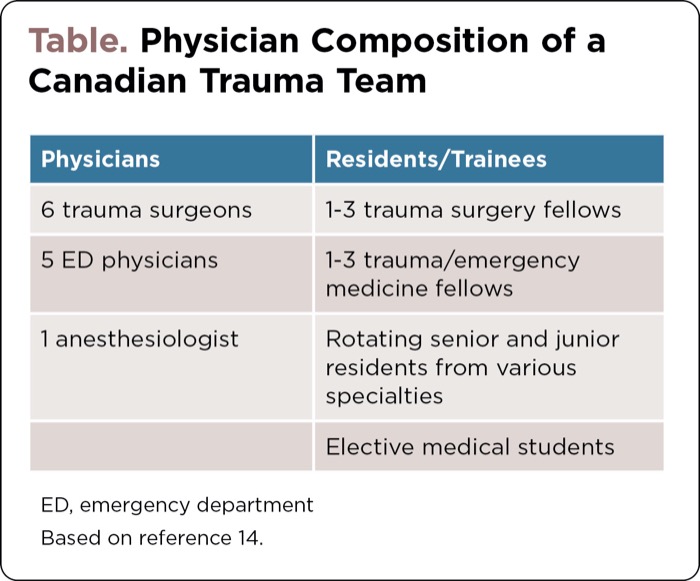

In many centers around the world, anesthesiologists are trained as trauma team leaders (TTLs) or traumatologists, although the composition of such trauma teams is variable.12 In Canada, the TTL is usually a trauma surgeon, anesthesiologist or ED physician (Table). The TTL works in the trauma bay and coordinates the resuscitation of acutely injured patients with a multidisciplinary team of surgeons, residents, nurses and respiratory therapists. The ED, surgical or anesthesia-trained TTLs bring their own skill set and qualifications to resuscitation, airway management, and diagnostic abilities using various imaging modalities, especially real-time point-of-care ultrasound. If a thoracotomy is required, the attending surgeon is present to assist with urgent intrathoracic surgical control of bleeding.11,13 The presence of a subspecialized TTL has been associated with improved patient outcomes in cases of major trauma, and a growing body of evidence endorses the safety and effectiveness of non–surgeon-led trauma resuscitation.14

| Table. Physician Composition of a Canadian Trauma Team | |

| Physicians | Residents/Trainees |

|---|---|

| 6 trauma surgeons | 1-3 trauma surgery fellows |

| 5 ED physicians | 1-3 trauma/emergency medicine fellows |

| 1 anesthesiologist | Rotating senior and junior residents from various specialties |

| Elective medical students | |

| ED, emergency department Based on reference 14. | |

Anesthesiologists are similarly part of the trauma service in many other countries. In Europe and Australia, trauma teams are diverse and typically include five to 15 members. Most teams consist of at least two ED nurses, an ED physician, an attending trauma surgeon, a surgery resident, an attending anesthesiologist and an anesthesiology resident, along with a radiology technician for chest and pelvis imaging in the trauma bay. In Denmark, the TTL is an orthopedic surgeon in 63.6% of trauma centers and an anesthesiologist in 36.4% of hospitals.15 In the United Kingdom, it has become a defined quality standard for senior anesthesiologists to be included as part of the trauma team. The British Royal College of Anaesthetists offers an entry path into anesthesia called the “Acute Care Common Stem,” which consists of a two-year training program combining acute care anesthesia, emergency medicine and intensive care medicine.16,17 In France, several academic institutions offer university diplomas in trauma anesthesia for anesthetists.18 Trauma anesthesiologists are trained as dynamic leaders with expertise in crisis resource management and have qualifications in intensive care, pain management and advanced resuscitation techniques important in acute resuscitation.

Over the last decade, anesthesiologists around the world have expanded their expertise and been formally trained as trauma anesthesiologists and TTLs by both surgeons and ED physicians, learning how to perform cricothyroidotomies, thoracostomies, endovascular occlusion procedures and appropriate imaging in trauma patients. These surgical skills only add to the anesthesia resuscitation tool kit to manage the most complicated surgical cases. A retrospective study of all trauma patients at the Montreal General Hospital between 1998 and 2015 found a significant reduction in mortality (absolute reduction, 1.25%; relative reduction, 16%) and ICU admissions (absolute reduction, 4.46%; relative reduction, 14%) when a multidisciplinary TTL model was introduced into the trauma team system.14 While anesthesiologists continue to lead COVID-19 airway teams, ICU airway teams, code blue airway teams and postoperative anesthesia care unit airway teams, the specialty is generally tasked with only reserve status in the ED in the United States.

Airway Management and Trauma Anesthesia in the United States

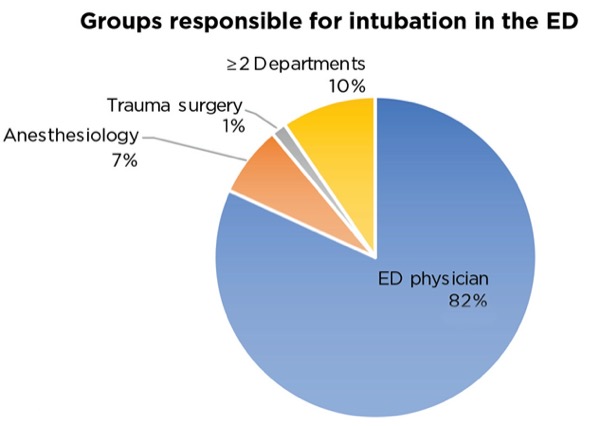

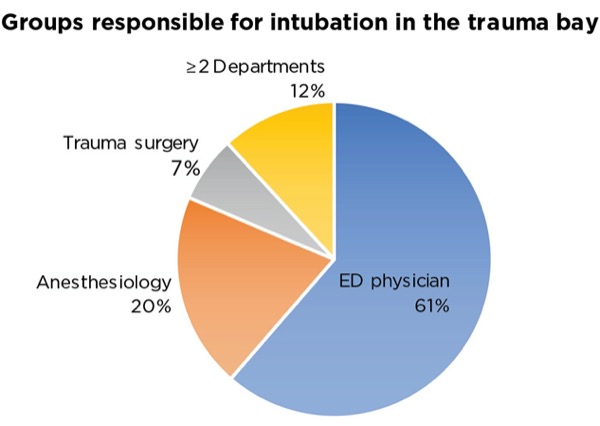

In urban cities, physicians have become more subspecialized, resulting in the contracted division of roles in trauma care despite trauma team members having overlapping proficiencies that may enhance team cooperation. During the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) primary survey, airway management is generally conducted by ED physicians with anesthesia support, while trauma surgeons evaluate life-threatening injuries in search of the culprit injury. One review discovered ED physicians performed at least 80% of all intubations in the ED and were primarily responsible for 61.4% of trauma ED intubations at all Level I trauma centers in the United States (Figure 3).19 This is a remarkable distinction for the United States, with most countries incorporating anesthesia at some point outside the OR in the trauma care pathway.

Anesthesiologists should be routinely present in the trauma bay to assist the service with vascular access, traumatic airways and massive transfusion events. Involvement of an anesthesiologist in the trauma bay also facilitates the seamless transition of care and handover to the operating theater, which is important in trying to avoid hypotensive episodes, clinically important missed injuries and secondary injury.20

The American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Trauma and Emergency Preparedness (COTEP) determined there is insufficient training in trauma anesthesia in residency programs across the United States.21 COTEP declared that residents must treat a minimum of 20 patients “undergoing procedures for complex, immediate life-threatening pathology,” which is not sufficient to manage severe unstable injuries with little time for optimization.21 Furthermore, there is a lack of formal education in at least 60% of anesthesia programs across the country, which creates critical gaps in knowledge of traumatic injury resuscitation, including the pathophysiology and treatment of hemorrhagic shock and trauma-induced coagulopathy.21 More importantly, the lack of exposure in the ED deprives anesthesia trainees with essential dynamic resuscitation experience in an acute uncontrolled environment and an opportunity to learn different approaches to emergent airway management.

Some authors have attributed the lack of exposure to an increased number of trained ED physicians, with the number of emergency medicine residency programs growing from 218 in 1979 to over 500 such programs today.22 During training, ED residents are required to “perform airway management on all appropriate patients, including those who are uncooperative, at the extremes of age, hemodynamically unstable and who have multiple co-morbidities, poorly defined anatomy, high risk for pain or procedural complications, or require sedation.”23 As this description can be easily observed in the care of trauma patients, many ED programs have formally included trauma airway experience into their curricula. Intubation by ED physicians is generally successful, with several trials revealing similar rates of intubation failure between anesthesiologists and ED physicians.24,25 The increasing use of video laryngoscopy in the ED significantly has increased the first-pass success rate in smaller centers.26,27 As a result, anesthesia residency programs, with no need for more airway management exposure, have not reacted in kind with consequential limited ED involvement.28

However, COVID-19 has shown that anesthesiologists can fill many roles in the critical care pathway and provide more than advanced airway support in the initial care of trauma patients, including advanced vascular access, acute sedation, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), arterial line insertion, thromboelastography and transfusion systems like the Belmont rapid infusion system, which are not regularly used in the ED. In many trauma centers, anesthesia models can be modified to guarantee ED coverage similar to airway management teams, which were adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic.29 Learning to effectively work in an acute care environment with a multidisciplinary group and function as both a resuscitation leader and team member is fundamental to anesthesiologist training and independent practice. While the added use of these devices and anesthesia proficiency in the ED is difficult to definitively study, the value of anesthesia to the trauma service and injured patient is an important unexplored resource for trauma bay resuscitation in the United States.

Moving Forward

With the use of advanced intraoperative monitoring techniques, resuscitation devices and pain management tools, which do not obstruct definitive surgery, anesthesiologists are slowly building the pieces of a trauma service with extensions outside the traditional OR setting. In severe trauma cases, the anesthesiologist assumes clinical leadership in the OR, while the surgeon searches for the source of bleeding. With the adoption and integration of ATLS principles into operative practice, anesthesiologists have adapted their own tools to support the damage control resuscitation mandate. TEE provides real-time information regarding cardiac function, REBOA (resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta) location, valvular disease and fluid status—information that is otherwise difficult to accurately obtain. It has been determined that a patient’s resuscitation requirements are often underestimated, and TEE may offer a more detailed approach to trauma resuscitation.30 However, providers should be careful in patients suspected of cervical spine and esophageal injuries in order to avoid iatrogenic harm. Basic TEE use to obtain standard views should become part of the ultrasound education in anesthesia residency programs and considered in anesthesia resuscitation to provide guidance for the trauma service.

Furthermore, the early use of regional anesthesia in traumatic injuries helps improve outcomes, recovery and patient flow.31 While its use has increased dramatically in patients with hip and rib fractures, regional anesthesia for other injuries (including abdominal, extremity and chest wall blocks) requires further investigation. Up to 77% of patients who sustain severe musculoskeletal trauma will report post-traumatic chronic pain, defined as pain lasting greater than three months from the time of injury. Almost 60% of multi-trauma patients with an Injury Severity Score of at least 16 have an extremity injury of some type, and 18% have both lower and upper extremity injuries.32 Most regional blocks can be considered except for proximal tibial fractures due to the higher risk for compartment syndrome. Regional anesthesia also may decrease length of stay in the ED and critical care unit, improve ability to perform neurologic evaluations, improve comfort and be cost-effective compared with moderate sedation.31,32 The Joint Commission Resources’ Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals now emphasizes the importance of early pain management in trauma patients.33 The presence of anesthesia in the trauma bay for all trauma admissions encourages earlier pain management, regional anesthesia nerve blocks and reduced in-hospital opioid use. As such, the regional anesthesia service should be added to the initial paging system for all non–life-threatening trauma cases, so nerve blocks are considered earlier along with a personalized inpatient pain management plan followed by the acute pain service.

Leading trauma anesthesiologists in the United States have moved a step further and proposed a practice model for acute care anesthesiology that parallels the acute care surgery service, called the perioperative surgical home.34 This would support an anesthesia team to be activated along with trauma surgery to staff urgent cases with experienced acute care attending anesthesiologists and encourage collaboration and communication during life-threatening scenarios. Anesthesia for patients in shock requires a thorough understanding of its pathophysiology and transfusion practices as well as specific considerations related to continuous assessment of physiologic reserves throughout the entire acute care period. A trauma team of professionals focused on trauma and critical care patients may improve patient care and safety in a Level I trauma center.35 Furthermore, studies have shown economic benefits with a coordinated care model, which is associated with reduced lengths of stay and improved outcomes in some instances.36 The acute care surgery anesthesia team would manage surgical and airway emergencies including acute strokes, trauma bay activations, bedside ICU cases, cardiac arrest or burn injuries, and implement goal-directed resuscitation strategies for each of these emergency scenarios.34

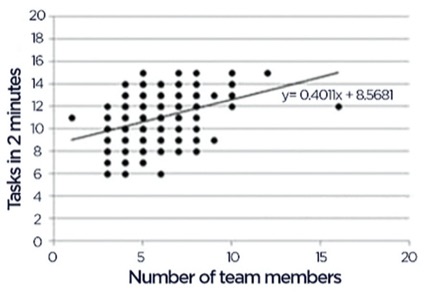

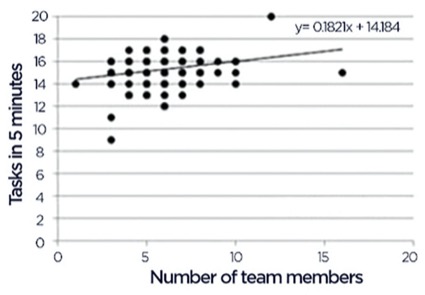

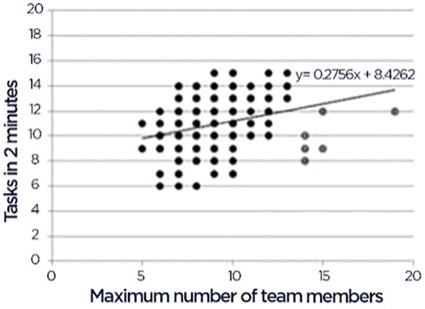

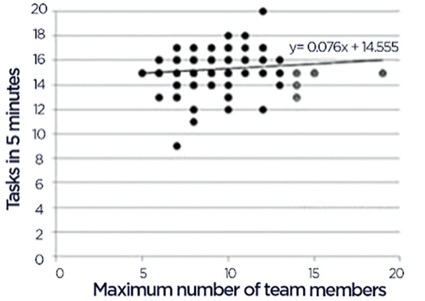

The optimal number of trauma team members remains elusive, although some studies have found a linear association with increasing team size and time to performance of significant tasks or efficiency of resuscitation (Figure 4).37 Efforts to expand the trauma anesthesia footprint outside the OR should begin with education. Early education in residency programs should include at least 50 trauma cases and emphasize the importance of multidisciplinary approaches to patient care with specific reference to trauma cases. The anesthesia trauma liaison should initiate their own trauma morbidity or quality improvement rounds to review anesthesia trauma cases, establish simulation and training programs for the residents, and offer airway and resuscitation support in the trauma bay to coordinate with the team and prepare for potential operative intervention.20

Leading physicians at COTEP also continue to advocate for an acute care trauma fellowship, which would include critical care rotations, high-acuity ED medicine (e.g., disaster medicine), trauma bay experience and prehospital transport. An interdisciplinary acute care team including surgeons, anesthesiologists and emergency physicians can help optimize care, minimize morbidity and ultimately provide a culture for enhanced team-based resuscitation and communication.

The Trauma Anesthesiology Society continues to expand through affiliations with the International Anesthesia Research Society and American Society of Anesthesiologists. The most problematic airway and resuscitation cases should be tasked to anesthesia providers as early as possible. Anesthesiologists are involved throughout the hospital stay of a trauma patient and should be present as shared stakeholders for airway management in at least 50% of trauma cases through a shared airway model with emergency medicine and trauma surgery. When providing support, anesthesia can assist with resuscitation, monitoring and invasive vascular access at the discretion of the TTL. Goal-directed TEE can be performed in the ED when point-of-care transthoracic echocardiography is not practical or diagnostic. Even high-risk medications typically organized by trauma nursing staff could be managed and administered by an anesthesiologist with pre-filled syringes.

The Trauma Anesthesiology Society continues to be an important resource for online discussion in regards to updated international guidelines, acute care anesthesia in austere environments, and multidisciplinary conferences. The systematic integration of anesthesia providers into trauma resuscitation in the ED will require cooperation among anesthesia societies, the promotion of advanced intraoperative anesthesia devices and increased trauma education among incoming trainees to enhance patient safety in challenging cases.

References

- Lowe RJ, Baker RJ. Organization and function of trauma care units. J Trauma. 1973;13(4):285-290.

- Fitts WT, Lehr HB, Bitner RL, et al. An analysis of 950 fatal injuries. Surgery. 1964;56:663-668.

- West JG, Trunkey DD, Lim RC. Systems of trauma care: a study of two counties. Arch Surg. 1979;114(4):455-460.

- Harvey JC. The emergency medical service systems act of 1973. JAMA. 1974;230(8):1139-1140.

- Epstein NE. Multidisciplinary in-hospital teams improve patient outcomes: a review. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5(suppl 7):S295-S303.

- Cowley RA. Trauma center. A new concept for the delivery of critical care. J Med Soc N J. 1977;74(11):979-987.

- West JG, Cales RH, Gazzaniga AB. Impact of regionalization. The Orange County experience. Arch Surg. 1983;118(6):740-744.

- Petrie D, Lane P, Stewart TC. An evaluation of patient outcomes comparing trauma team activated versus trauma team not activated using TRISS analysis. Trauma and Injury Severity Score. J Trauma. 1996;41(5):870-873.

- Breckwoldt J, Klemstein S, Brunne B, et al. Expertise in prehospital endotracheal intubation by emergency medicine physicians-Comparing ‘proficient performers’ and ‘experts.’ Resuscitation. 2012;83(4):434-439.

- American College of Surgeons, Committee on Trauma. ATLS Advanced Trauma Life Support: Student Course Manual, 10th Ed. American College of Surgeons; 2018.

- Engels PT, Paton-Gay JD, Tien HC. Trauma team structure and organization. Trauma Team Dynamics. 2016:47-54.

- Belhumeur V, Malo C, Nadeau A, et al. Trauma team leaders in Canada: a national survey. Trauma. 2020;22(2):126-132.

- Hjortdahl M, Ringen AH, Naess AC, et al. Leadership is the essential non-technical skill in the trauma team – results of a qualitative study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17(1):48.

- Lavigueur O, Nemeth J, Razek T, et al. The effect of a multidisciplinary trauma team leader paradigm at a tertiary trauma center: 10-year experience. Emerg Med Int. 2020;2020:8412179.

- Weile J, Nielsen K, Primdahl SC, et al. Trauma facilities in Denmark - a nationwide cross-sectional benchmark study of facilities and trauma care organisation. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2018;26(1):22.

- Acute Care Common Stem (ACCS). The Royal College of Anaesthetists. 2021. www.rcoa.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2021-06/2021%20Curriculum%20for%20ACCS%20Training%20v1.0.pdf

- Guidelines for the Provision of Anaesthetic Services (n.d.). Retrieved from https://rcoa.ac.uk/safety-standards-quality/guidance-resources/guidelines-provision-anaesthetic-services

- Diplomes d’Universite en Sante Thrombose et Hemostase Clinique. 2014. Accessed August 22, 2022. http://offre-de-formations.univ-lyon1.fr/parcours-690/thrombose-et-hemostase-clinique.html#

- Chiaghana C, Giordano C, Cobb D, et al. Emergency department airway management responsibilities in the United States. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(2):296-301.

- Levitan RM, Rosenblatt B, Meiner EM, et al. Alternating day emergency medicine and anesthesia resident responsibility for management of the trauma airway: a study of laryngoscopy performance and intubation success. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43(1):48-53.

- Kaslow O, Kuza CM, McCunn M, et al. Trauma anesthesiology as part of the core anesthesiology residency program training: expert opinion of the American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Trauma and Emergency Preparedness (ASA COTEP). Anesth Analg. 2017;125(3):1060-1065.

- Chang B, Urman RD. Non-operating room anesthesia: the principles of patient assessment and preparation. Anesthesiol Clin. 2016;34(1):223-240.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Number of accredited programs by academic year. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Reports/Report/3

- Bushra JS, McNeil B, Wald DA, et al. A comparison of trauma intubations managed by anesthesiologists and emergency physicians. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(1):66-70.

- Sakles JC, Douglas MJK, Hypes CD, et al. Management of patients with predicted difficult airways in an academic emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2017;53(2):163-171.

- Sakles JC, Patanwala AE, Mosier JM, et al. Comparison of video laryngoscopy to direct laryngoscopy for intubation of patients with difficult airway characteristics in the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med. 2014;9(1):93-98.

- Michailidou M, O’Keeffe T, Mosier JM, et al. A comparison of video laryngoscopy to direct laryngoscopy for the emergency intubation of trauma patients. World J Surg. 2015;39(3):782-788.

- Teale KF, Selby IR, James MR. General anaesthesia in accident and emergency departments. J Accid Emerg Med. 1995;12(4):259-261.

- Gong Y, Cao X, Mei W, et al. Anesthesia considerations and infection precautions for trauma and acute care cases during the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations from a task force of the Chinese Society of Anesthesiology. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(2):326-334.

- Nowack T, Christie DB. Ultrasound in trauma resuscitation and critical care with hemodynamic transesophageal echocardiography guidance. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019;87(1):234-239.

- Gadsden J, Warlick A. Regional anesthesia for the trauma patient: improving patient outcomes. Local Reg Anesth. 2015;12(8):45-55.

- Galvagno SM, Smith CE, Varon AJ, et al. Pain management for blunt thoracic trauma: a joint practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma and Trauma Anesthesiology Society. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(5):936-951.

- Joint Commission Resources. Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals. Joint Commission Resources; 2017.

- McCunn M, Dutton RP, Heim C, et al. Trauma anesthesia contributions to the acute care anesthesiology model and the perioperative surgical home. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2016;6:22-29.

- Dutton RP, Cooper C, Jones A, et al. Daily multidisciplinary rounds shorten length of stay for trauma patients. J Trauma. 2003;55(5):913-919.

- Dutton RP, Stansbury LG, Leone S, et al. Trauma mortality in mature trauma systems: are we doing better? An analysis of trauma mortality patterns, 1997-2008. J Trauma. 2010;69(3):620-626.

- Maluso P, Hernandez M, Amdur RL, et al. Trauma team size and task performance in adult trauma resuscitations. J Surg Res. 2016;204(1):176-182.

Copyright © 2022 McMahon Publishing, 545 West 45th Street, New York, NY 10036. Printed in the USA. All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction, in whole or in part, in any form.

Download to read this article in PDF document:![]() Anesthesia in the Trauma Bay

Anesthesia in the Trauma Bay

Please log in to post a comment