I was the third of four anesthesiologists in our group to fall ill in little more than a year. It was 2019, and I had just worked up the courage to ask for a slightly reduced weekend call load. As my family’s breadwinner, a wife, a mother of two young daughters and a full-time pediatric anesthesiologist in a newly constructed children’s hospital, I was chronically exhausted and knew I had been doing too much for far too long.

As one anesthesiologist after another became seriously ill, the remaining members of our group were forced to take on more call. During those years, our weekday calls lasted 24 hours and the weekend calls were 72 hours, distributed among a shrinking pool of 10 full-time physicians. The schedule was brutal but not unusually so for anesthesiology, and the options for improving it were limited. More staff couldn’t be hired quickly enough to ease the immediate load, and volume growth in our high-acuity practice outpaced our ability to recruit. Additionally, locum tenens physicians are prohibitively expensive to hire and may not be able to properly cover highly specialized cases.

Our group’s experience, coupled with my own ordeal following a sudden devastating diagnosis of stage IV lung cancer, highlights why our profession needs to start taking better care of its own.

We need to plan ahead for the inevitable reality that a reduced workload and lessened or suspended call may be necessary at different periods throughout an anesthesiologist’s life: the birth of a child, the death of a loved one, personal illness or injury, and/or advanced age. According to the literature, some degree of reduced capacity for clinical work is likely to occur in up to one-third of anesthesiologists over the course of their careers (Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2017;30[2]:217-222). It’s a well-established fact that sleep exerts an immune-supportive function, and that sleep deprivation alters immune parameters “leading to a chronic inflammatory state and an increased risk for infectious/inflammatory pathologies, including cardiometabolic, neoplastic, autoimmune and neurodegenerative diseases” (Commun Biol 2021;4[1]:1304).

There must be a better way—a more humane way—to structure anesthesiology staffing and the delivery of anesthesia care.

My Story

Here’s what happened to me, a previously healthy 45-year-old woman. The long hours of constant vigilance, performing procedures and coordinating care while also raising a family took a toll. The increasing call burden was the last straw. I felt that something was going to snap, either my marriage or me. Then during one call night, I felt just above my clavicle a solitary swollen lymph node.

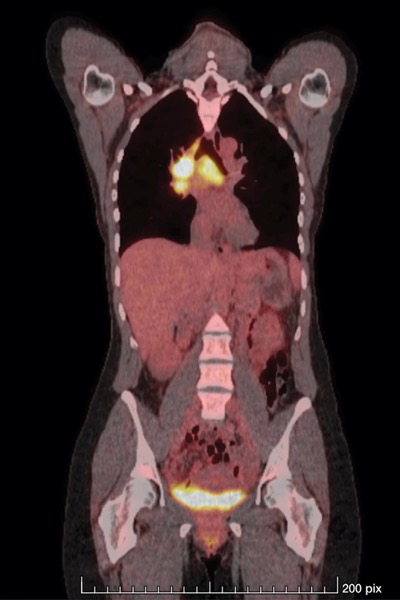

Because of the location of the node, I knew that a gastrointestinal or pulmonary malignancy was likely. A quick succession of urgent imaging procedures ensued; a suspicious ultrasound led to a CT scan. Soon after, I saw my doctor’s missed call on my phone. I frantically called him back from the nurses station, and received the full blow. My doctor sounded almost as blindsided as I had felt. His voice faltered as he told me the diagnosis: “advanced-stage lung cancer.”

A few minutes after this life-changing call, I tearfully related the news to our chairman and was placed on immediate medical leave. Tragically, within a few days of my own diagnosis, the fourth anesthesiologist in our group to fall ill was also diagnosed with advanced cancer, and died shortly thereafter.

This was the darkest hour in our small practice. Two cancer diagnoses, resulting in one death and another terminal diagnosis, shook the department. I have no idea how my colleagues coped with the increased call burden, as I was too distraught, facing what I believed would be my own impending demise. I cannot imagine what it must have been like for them to come into work during those days. Fortunately, some of our group members returned from sick leave, and our department gradually began hiring more anesthesiologists, providing essential relief.

After four weeks, my oncologist finally gave me some much-needed good news: Next-generation sequencing revealed that my tumor was driven by a rearranged oncogene known as the anaplastic lymphoma kinase or ALK gene. This meant that I would be able to receive targeted therapy, which in many cases has obviated the need for chemotherapy and radiation. Thanks to recent research breakthroughs, many patients with ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) now are living more than six years, and some even more than 10 years.

Within two weeks of starting treatment, my swollen lymph nodes started disappearing. Like other patients on first-line therapy for ALK-rearranged NSCLC, I suffered from myalgias, severe fatigue and anemia as side effects of treatment. The fatigue that I experienced felt how I imagine narcolepsy must feel, as I found myself suddenly falling asleep while sitting up. Despite the side effects, I was responding well to treatment, so my oncologist and I started planning my return to work.

Neither of us believed I could or should resume my pre-diagnosis workload. Call was problematic, as the lack of sleep and acute stress of emergency surgeries could be unsafe in the setting of such severe fatigue. I knew I could still work, however, and my oncologist also wanted that for me.

I learned that because of the lung cancer diagnosis, my continued employment was protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act, which enabled me to apply for workplace accommodations. My oncologist recommended that I be limited to no more than 10 hours per day, four days per week, with no call. She also requested frequent breaks for drinking water and going to the bathroom, as I needed to drink almost a gallon of water daily to protect my kidneys from the targeted agent. Fortunately, my department accepted these accommodations with an appropriate reduction in salary.

Workplace accommodations saved my livelihood and preserved my personal and professional identity just as the targeted agent saved my physical life. Being able to return to work with reduced hours helped me regain the dignity and normalcy that cancer threatened to take away. Returning to work was like someone giving me back everything I believed I had lost: my vocation, my skill, my community and my identity in this world.

These accommodations meant that, for the first time in over 10 years, my schedule was regular and predictable enough for me to engage in regular exercise and get enough sleep. The positive physiologic effects of physical exercise, consistent sleep, working in a supportive and nurturing environment, and the restoration of a purpose-driven life supported my health tremendously. By the sixth month of treatment, I officially had no evidence of disease and have remained so for over four years. It is as though, once given optimal conditions, my immune system synergized with treatment and restored my health.

Must We Wait for a Crisis?

The question remains: Must we become disabled in order to attain better working conditions? Do our bodies need to be ablaze with disease before we dare ask for a lessened workload? Unfortunately, the literature is silent on these issues. Articles regarding “accommodations” in the anesthesiology literature are limited to accommodations for residents, usually with regard to childbirth and breastfeeding.

We need mechanisms in place to supplement the anesthesiology workforce with temporary personnel in a cost-effective manner. Of course, this would require planning, and the ability to expand and contract the workforce in a dynamic manner.

If competing hospitals in shared geographic areas could work together to develop staffing cooperatives, they might be better equipped to absorb shortages without placing undue burden on their own staff or their own bottom lines. Participating anesthesiologists could be credentialed and get experience at each hospital in the cooperative, so that they could be deployed quickly to fill the gap in the event of a sudden need for personnel. This would require each participating hospital to staff above normal demand level to create a pool of backup anesthesiologists, but it could provide coverage at short notice over a region without the need to pay exorbitant “locums” fees or overwork the remaining staff.

Our workplaces need to change their fundamental attitudes and regard us more holistically. We are not pawns on the hospital administration chessboard. We are humans who live within family structures and are susceptible to illness and injury like everyone else. With some flexibility and support, we can remain productive and thrive, even when we as physicians inevitably become patients.

Castro-Frenzel is an assistant professor of anesthesiology at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine, and a staff anesthesiologist at Nemours Children’s Health, both in Orlando, Fla.

Editor’s note: The views expressed in this commentary belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the publication.

Please log in to post a comment

Two things:

1). "with an appropriate reduction in salary." Many covered people are not willing to take a salary cut.

2). While humane planning sounds good, the 10 doc group the author was in facilitated humane treatment.

I've worked in 40 doc groups at Medical Meccas where this type of accommodation is standard.

I've also worked in 5 and 2 doc groups where this type of accommodation is not possible.

Small rural hospitals have no way to do this.

This is real. My department required me to return to work 2 1/2 weeks after a combined hip/knee total arthroplasties. Had to be driven to work. No time off for extended bout of interstitial pneumonitis. No accomodation until I semi-retired.

Great article! I'm sorry for your plight.

It's VERY difficult times in anesthesia staffing requiring "hospital funding"/stipends of private groups, esp small groups,(which are rapidly disappearing) to fund the increase in salary and bonuses needed.

I had severe depression and emotional issues which are sadly way less recognized than cancer or pregnancy in our society.

Leaving a call position as you did, saved my life.

As you note, sleep, exercise,proper diet, cognitive therapy and "proper"self care(which as physicians we forfeit)extended my career and my life.

I recommend only 8 hrs per day and 5 days per week.

"Workaholics" is synonymous with anesthesiologists? This to me is true.

We sign up for it in the beginning and accept it.

We should not.

Live healthier.

Start today.