University of Colorado School of Medicine

Attending Physician

Denver Health and Hospital

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Aurora

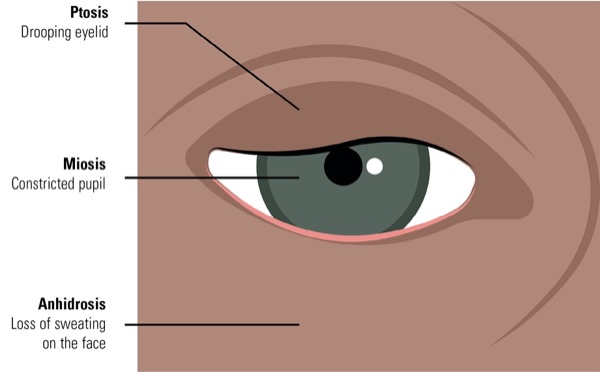

Interscalene blocks (ISBs) are commonly used during and after surgery to provide analgesia for the upper arm and shoulder. Horner syndrome is a known complication of ISB, caused by the spread of local anesthetic to the cervical sympathetic chain resulting in an ipsilateral stellate ganglion block. Typically, symptoms of Horner syndrome—which may include ptosis, myosis, anisocoria, anhidrosis and enophthalmos—appear immediately after the block is placed, with some reports of delays up to 40 minutes (Figure 1).

We present an unusual case of delayed Horner syndrome that developed more than 15 hours after a single-shot injection of an ISB for rotator cuff repair.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old woman presented to the emergency department at midnight following successful operation for right rotator cuff repair that morning. She complained of a droopy right eyelid, unequal pupil size with right-sided constriction, and right facial numbness. Her past medical history was remarkable only for anxiety and mild asthma, for which she used a budesonide/formoterol (Symbicort, AstraZeneca) inhaler daily and albuterol as needed.

The patient had received an ultrasound-guided ISB at 7 a.m. for postoperative pain control following planned right rotator cuff repair. The anesthesiologist achieved good ultrasound visualization of the C5-C7 nerve roots and injected 0.5% bupivacaine, 20 cc, without difficulty. The patient stated that she felt short of breath immediately after the block and felt as though she could not swallow or speak, but she was swallowing and speaking clearly. She believed these symptoms were due to her underlying anxiety, was able to take deep breaths and noted prompt resolution of her symptoms.

After block placement, the patient was brought to the OR and general anesthesia was induced with intravenous lidocaine, propofol and rocuronium. Mask ventilation was easy, and she was intubated without difficulty with a 7.0 endotracheal tube. The patient was placed in the beach chair position and surgery proceeded uneventfully. The patient was awakened, the endotracheal tube was removed, and she was brought to the PACU, where she recovered without issues. She was discharged home free of pain, with her right shoulder, arm and hand completely numb. Neither the anesthesiology team nor the PACU nurses noted any concerns or signs or symptoms of Horner syndrome.

Approximately 10 p.m. that evening, the patient noted the onset of right-sided ptosis, myosis, enophthalmos and numbness/tingling along the right side of her face consistent with Horner syndrome. None of these symptoms had been present earlier in the day. She presented to the emergency department and anesthesiology was consulted. On examination, the patient was beginning to regain feeling in her fingers and arm, and she noted some pain in her shoulder at the operative site. She was not short of breath and had no difficulty with speaking or swallowing.

Because of the delayed presentation of the patient’s symptoms, neurology was consulted and a CT scan was performed that demonstrated no abnormality. Horner syndrome was attributed to the ISB, and spontaneous resolution was anticipated as the block continued to wear off. The patient was discharged home and her symptoms resolved completely over the next 24 hours.

Discussion

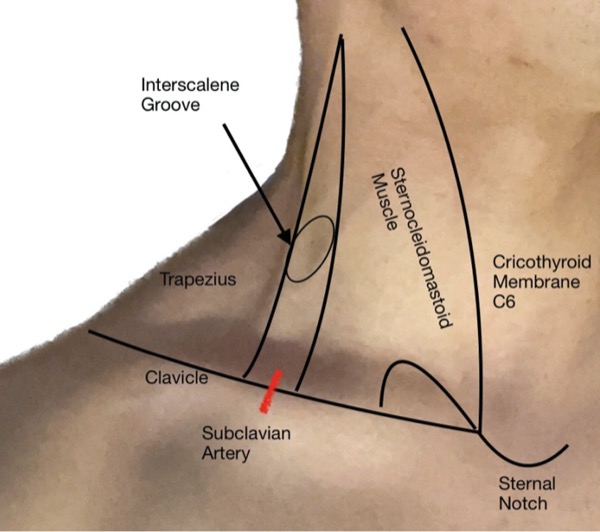

Placement of an ISB, with or without a continuous catheter, is indicated for analgesia after upper arm and shoulder surgery to block the nerve roots of the brachial plexus, which run in the interscalene groove at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. The ISB is a reliable block with a 99% success rate when performed under ultrasound guidance and a reported complication rate of 2.3%.1 The common risks of any peripheral nerve block also apply to ISB, including local anesthetic toxicity, hematoma, bleeding and nerve injury.

The most common complication of ISB is phrenic nerve paralysis, with a reported frequency of 90% or higher when the block is performed under nerve stimulation guidance, but only about 45% when ultrasound is used for guidance and lower volumes of local anesthetic are used. The incidence of phrenic nerve paralysis may be further reduced to about 21% when lower volumes of local anesthetic are injected into the interscalene groove (Figure 2) at the C6 level of the cricothyroid membrane, and spread is limited to the C5 and C6 nerve roots.2,3

Other known complications of ISB are Horner syndrome, hoarseness, pneumothorax, total spinal or epidural anesthesia, and numbness in the posterior auricular nerve area. Horner syndrome is caused by local anesthesia spread to the cervical sympathetic chain causing an ipsilateral stellate ganglion block, with a reported incidence in 6% to 12% of cases.4 Hoarseness may occur if local anesthetic numbs the recurrent laryngeal nerve, and is seen in 40% to 60% of cases.5,6 Both the stellate ganglion and the recurrent laryngeal nerve are in close proximity to the brachial plexus in the lower neck, and are easily numbed during injection for ISB. The effects are self-limiting and typically resolve as the block wears off.

Previous case reports have documented delayed presentation and long-lasting symptoms of Horner syndrome lasting up to a year after continuous interscalene nerve catheter placement.7 Reports of delayed presentation and/or prolonged duration of Horner syndrome following a single-shot ISB are less common.8 In any such case, other causes of Horner syndrome must be ruled out, which may include transient ischemic attack, stroke, neck hematoma, infection or any kind of mass in the area. Symptoms may also be caused by trauma to the carotid artery, subclavian artery or jugular vein, or by poor positioning of the neck during surgery. Imaging such as CT or MRI is indicated to rule out other potential causes of prolonged Horner syndrome after ISB.9

After other causes of Horner syndrome have been ruled out, a patient may be reassured that symptoms will resolve with time, require no treatment and have no long-term sequelae.

Conclusion

Our patient presented with Horner syndrome that did not develop until approximately 15 hours after ISB with a single-shot injection of bupivacaine, placed under ultrasound guidance. In view of the delayed presentation, neurologic consultation and CT scan evaluation were obtained, but no other cause of the patient’s symptoms was found. Full resolution of her symptoms was achieved over the next 24 hours. This case demonstrates that complications or side effects of ISB may take time to manifest. While other causes must be ruled out, even prolonged or delayed effects of ISB such as Horner syndrome may be expected to resolve completely over time.

The Frost Series is named in recognition of Elizabeth Frost, MD, who started this feature in the early 1980s.

Sibert, a past president of the California Society of Anesthesiologists and member of the Anesthesiology News editorial advisory board, is the medical editor of “The Frost Series.” Authors who wish to submit a case to her may send it to FrostCaseSubmission@gmail.com. Please limit text to about 1,200 words and include an image, if possible.

References

- Takayama K, Shiode H, Ito H. Ultrasound-guided interscalene block anesthesia performed by an orthopedic surgeon: a study of 1322 cases of shoulder surgery. JSES Int. 2022;6(1):149-154.

- Riazi S, Carmichael N, Awad I, et al. Effect of local anaesthetic volume (20 vs 5 ml) on the efficacy and respiratory consequences of ultrasound-guided interscalene brachial plexus block. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(4):549-556.

- Palhais N, Brull R, Kern C, et al. Extrafascial injection for interscalene brachial plexus block reduces respiratory complications compared with a conventional intrafascial injection: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Br J Anaesth. 2016;116(4):531.

- Stasiowski M, Zuber M, Marciniak R, et al. Risk factors for the development of Horner’s syndrome following interscalene brachial plexus block using ropivacaine for shoulder arthroscopy: a randomised trial. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2018;50(3):215-220.

- Zisquit J, Nedeff N. Interscalene block. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Accessed July 5, 2023. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/ NBK519491/

- Jeong JS, Kim YJ, Woo J-H, et al. A retrospective analysis of neurological complications after ultrasound guided interscalene block for arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Anesth Pain Med. 2018;13(2):184-191.

- Ekatodramis G, Macaire P, Borgeat A. Prolonged Horner syndrome due to neck hematoma after continuous interscalene block. Anesthesiology. 2001;95(3):801-803.

- Hakim M, Beltran RJ, Khawaja AA, et al. Prolonged Horner’s syndrome after intraoperative interscalene block. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2017;21(4):468-471.

- Bardorf C. Horner’s syndrome. Medscape. Accessed July 5, 2023. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/ 1220091-overview

Please log in to post a comment

This is but one of the numerous iatrogenic “side effects” caused by nerve blocks. Fortunately it wasn’t life-threatening and didn’t cause lasting harm. Furthermore, nerve blocks often cause toxic or mechanical nerve damage and are unreliable, because their effects may “wear off” before surgery is complete, so that the resulting uncontrolled surgical nociception activates the surgical stress syndrome, which defeats the purpose of the bock. In addition, the installation of nerve blocks consumes valuable time and requires expensive ultrasound equipment and nursing support. Surgeons sometimes install local analgesic blocks at the conclusion of surgical procedures to prevent post-operative pain, and I have seen anesthesiologists go to the trouble of installing “continuous epidural” catheters but not activating them until the conclusion of surgery for fear of causing “hypotension” even though mild hypotension during surgery usually reflects effective nociception control that improves outcome. When the blocks are installed AFTER the surgery is complete, they do not prevent the surgical stress syndrome, even though they may postpone postoperative pain. I often installed and activated epidural catheters BEFORE surgery by having patients sit up on the operating table, but I took care to confirm that the analgesia was taking effect before I proceeded with elective intubation and general anesthesia. This generally produced excellent outcomes provided the epidural analgesia was maintained effectively throughout the procedures. However, THERE’S A BETTER WAY. Supplementation of general anesthesia with modern synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and Sufentanil combined with “permissive” hypercarbia in the range of 50-100 torr as monitored by modern capnography offers a safer, simpler, more predictable and reliable means to control surgical nociception and optimize surgical outcome. Hypercarbia accelerates opioid clearance and counteracts opioid respiratory depression. Combinations of hypercarbia and opioid analgesia substantially improve microvascular perfusion and organ safety during anesthesia, which prevents the surgical stress syndrome and optimizes surgical outcome. Read the classic book written 100 years ago by Dr. George Washington Crile called “Anoci-Association.” Also read my published review of CO2 pathophysiology entitled “Four Forgotten Giants of Anesthesia History.” Both are available free of charge via the Internet. www.stressmechanism.com.