A patient who presents for surgery with a history of difficult intubation commands the attention of any anesthesiologist. Questions immediately arise. What technique was used in the past to achieve success? Is better equipment available today? Was the patient truly difficult to intubate, or was operator inexperience perhaps a contributing factor?

We describe the case of a patient with a history of very difficult intubation in two prior surgeries, who proved not to be difficult to intubate on a third occasion. We analyze what could be learned from the first two instances, discuss how the use of a video laryngoscope does not automatically guarantee intubation success, and consider how the choice among different laryngoscope blades—whether for direct or video laryngoscopy—may improve the odds of successful intubation.

Case Presentation

A 52-year-old woman with a body mass index of 42.7 kg/m2 presented to an academic teaching hospital for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Her medical history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, Graves’ disease and breast cancer three years previously.

Her anesthetic history was significant for difficulty with tracheal intubation, requiring multiple attempts on two previous occasions. The patient described a severe sore throat and prolonged hoarseness for weeks after both operations, noting that the throat pain was worse than her incisional pain and made it difficult for her to function in her occupation as a teacher.

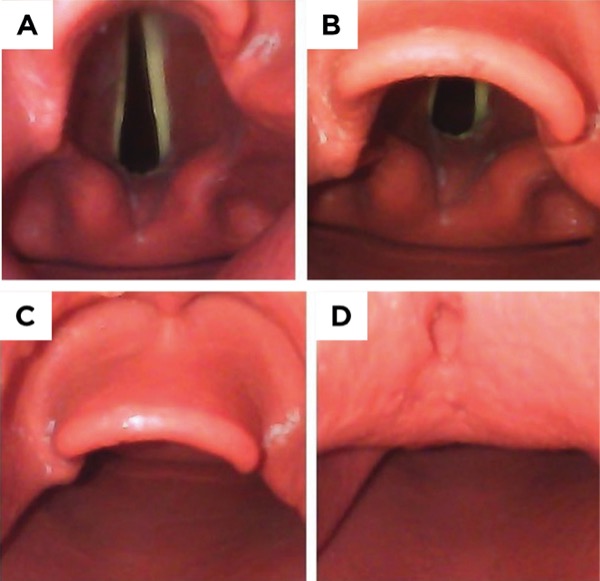

The patient’s first operation three years before was a left subcutaneous mastectomy with immediate reconstruction. After induction of anesthesia, the anesthesia team documented moderate difficulty in ventilating the patient by mask. An oral airway and two-handed mask technique were required. A GlideScope (Verathon) was used for the first attempt, but an optimal view of the vocal cords was not achieved. The patient was repositioned with a shoulder roll for increased neck extension, but a second attempt achieved only a view of the epiglottis (Cormack-Lehane grading system, Figure 1; see 1C) and no success in passing either an endotracheal tube (ETT) or an intubating bougie. Two further attempts were made with a fiberoptic bronchoscope but failed to obtain a view of the vocal cords. A fifth attempt was made with a GlideScope by a different anesthesiologist, obtaining a partial view of the glottis (Figure 1, see 1B) and successfully inserting a 6.5 ETT with the aid of a rigid stylet.

One year later, the patient presented for revision of the left breast reconstruction. The anesthesia team again described moderate difficulty with mask ventilation requiring two hands. The initial laryngoscopy by a first-year anesthesiology resident using a GlideScope revealed no view either of the epiglottis or glottis (Figure 1, see 1D). The attending anesthesiologist was also unable to obtain a view of the glottis with the GlideScope. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was attempted both through the mouth and nares, but was unsuccessful with difficulty attributed to copious secretions. An intubating laryngeal mask airway (the LMA Fastrach, Teleflex) was then inserted. A 6.5 ETT was passed through the LM airway and into the trachea with fiberoptic visualization of the vocal cords, which were described as small. The team recommended difficult airway precautions and fiberoptic intubation for any future anesthetics.

The patient presented for screening colonoscopy one year after the second surgery. Because of the previous difficulties with intubation and mask ventilation, the anesthesia team decided to perform awake fiberoptic intubation, which was accomplished with topical anesthesia and minimal sedation.

On the day of surgery for the laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, the patient acknowledged that she was anxious primarily due to the prior issues with her airway management. She had found the awake fiberoptic intubation to be a highly unpleasant experience, which she recalled completely. She understood that awake intubation might be necessary again, but asked whether there might be any way to avoid it.

Physical examination of the patient’s airway revealed that she had a short neck but a normal thyromental distance with good neck extension and mobility, and she could open her mouth widely. Her uvula could be partially seen, consistent with a Mallampati II score. We decided to proceed with induction of general anesthesia before intubation, and the patient expressed relief. Preparations were made for possible difficult intubation, with a fiberoptic bronchoscope in the OR together with a video laryngoscope and a selection of laryngoscope blades and bougies. We gave the patient IV premedication with 0.2 mg of glycopyrrolate (for reduction of secretions) and 2 mg of midazolam.

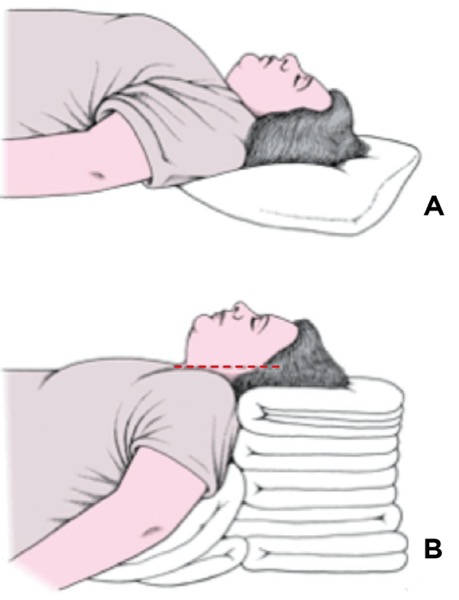

In the OR, we took care to place the patient comfortably in the sniffing or Magill position, with the back of the bed elevated approximately 30 degrees, her head on a pillow and her neck extended on the atlas with horizontal alignment of her earlobe and sternal notch (Figure 2, positioning of the obese patient, see 2B). After induction of general anesthesia and muscle relaxation, we found that ventilation by mask was easy with one hand and there was no need for an oral airway.

Using a video laryngoscope with a Macintosh 4 blade inserted into the vallecula, we were able to see the patient’s arytenoid cartilages. By advancing the blade and lifting the epiglottis, we were able to obtain a full view of the vocal cords, which were small and anteriorly located. We elected to insert a gently curved 10 Fr pediatric bougie through the vocal cords and then advanced a 6.5 ETT easily over the bougie. Tube placement was confirmed with bilateral breath sounds and end-tidal carbon dioxide.

The rest of the case proceeded uneventfully. In the PACU, the patient denied sore throat and was able to speak normally. She was discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 2 expressing satisfaction with her anesthesia care. We gave her a letter for future reference describing how her intubation was successfully accomplished, and made detailed notes in her record.

Discussion

Due to the excellent documentation of the patient’s first two intubations, we believed that we had a good sense of what the problems may have been and what could be done to improve the likelihood of success. Since both teams had been able to ventilate the patient by mask, albeit with some difficulty, we did not feel that an awake intubation was indicated.

We suspected that the patient may have been positioned flat on the OR table rather than in the sniffing position, as the completely supine position for induction was the institutional norm at the time. We also knew from the first intubation note that placement of a shoulder roll for hyperextension of the neck had not improved visibility. We were reminded of the comments of Cormack and Lehane in 1984, in their classic article on difficult intubation in obstetrics:

“Probably the commonest cause of difficulty for the beginner is not putting the patient’s head in the Magill position. Magill1 showed that the natural tendency to extend the neck is a mistake, since it actually makes intubation more difficult. On the contrary, the neck should be flexed, which ‘may require the insertion of a pillow’, whilst ‘the head is extended on the atlas’. Thus the two main requirements had been clearly stated in 1930…Magill’s original description has never been bettered and can be recommended to all anaesthetists.”2

The 30-degree head-up position has been shown to facilitate intubation success and prolong the time to oxygen desaturation in multiple studies,3 and we advocate its routine use, especially in patients with a high BMI. It may also reduce the risk for passive regurgitation and aspiration.

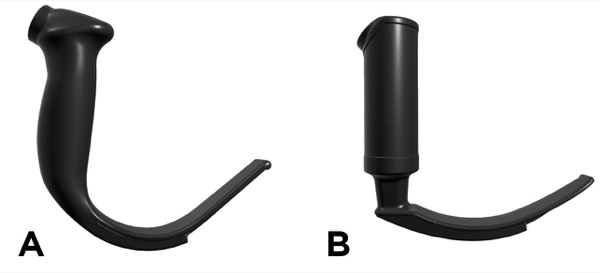

We hypothesized that the use of a different laryngoscope blade might facilitate easier intubation. Although the type of blade was not specified in the notes from the first two anesthetics, it seemed likely that the standard GlideScope hyperangulated blade was used (Figure 3A). This blade with a 60-degree curvature was the original design for indirect laryngoscopy developed in the late 1990s by Canadian surgeon John Pacey, MD. Soon after, Berci and Kaplan worked with KARL STORZ to develop the C-MAC, which utilizes video laryngoscopy with a less curved Macintosh-style blade (Figure 3B).4 In subsequent years, multiple blade styles for video laryngoscopy were developed by KARL STORZ, Verathon and other manufacturers, so that anesthesiologists today have a full range of blade choices.

Knowing that the hyperangulated blade had not led to easy intubation in this patient’s case, we decided to use a Macintosh blade for video laryngoscopy. It allows the options of placing the blade tip in the vallecula or using it as we would a straight Miller blade to elevate the epiglottis. By lifting the epiglottis, we were able to obtain a full view of the glottis and had no trouble inserting the ETT. We elected to use a flexible 10 Fr pediatric bougie because it could be easily angled up toward the glottis, which was anterior, and because it would have been easy to pass an even smaller tube over the bougie if the 6.5 ETT had proved hard to advance.

We were also influenced in our choice of a Macintosh blade by the report of Maassen and colleagues, who studied intubation with video laryngoscopy in patients with a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2.5 They compared the original GlideScope, KARL STORZ V-MAC and McGrath video laryngoscopes, finding that the Macintosh-style blade resulted in fewer attempts and shorter times to successful intubation, and reduced the need for use of a rigid stylet, which carries its own risks for airway trauma. Our personal experience coincides with that of Maassen and colleagues. We note also that the flange of the Macintosh blade facilitates sweeping the tongue to the side out of the visual path and opening up more space to pass the ETT.

Even when the hyperangulated 60-degree blade produces an excellent view of the glottis, passing the tube may not be easy. In an excellent review, Doyle notes that users may achieve a perfect glottic view with the hyperangulated blade but experience difficulty advancing the ETT into the glottic aperture because of the tube abutting against the anterior tracheal wall. Paradoxically, “the position that provides the best glottic view is generally not the position that makes intubation the easiest.”6 In contrast, the Macintosh blade does not lift the larynx as far anteriorly, and reduces the incidence of the tube getting caught on the anterior tracheal rings.

Conclusion

Insanity has been defined (in a quote often misattributed to Albert Einstein) as doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result. In the case of airway management, when you are lucky enough to know what didn’t work in the past, you have the opportunity to approach the case differently. While the hyperangulated 60-degree blade may produce the best view of the glottis in situations where there is limited neck extension or mouth opening, that was not the problem in our patient’s case. She had an anterior larynx and a high BMI, problems that may have been exacerbated by the fully supine position and hyperextension of the neck during her first two anesthetics.

In this case, we believed that a different approach might make the patient’s airway much easier to manage while giving her a more pleasant anesthetic experience, and we attribute success to these points:

- careful review of prior airway management notes;

- positioning the patient in the classic “sniffing” or Magill position, with the head of the bed raised 30 degrees, avoidance of neck hyperextension and horizontal alignment of the earlobe and sternal notch; and

- utilizing a Macintosh blade for video laryngoscopy as opposed to the hyperangulated blade that was used in previous unsuccessful attempts.

The Frost Series is named in recognition of Elizabeth Frost, MD, who started this feature in the early 1980s.

Sibert, a past president of the California Society of Anesthesiologists and member of the Anesthesiology News editorial advisory board, is the medical editor of “The Frost Series.” Authors who wish to submit a case to her may send it to FrostCaseSubmission@gmail.com. Please limit text to about 1,200 words and include an image, if possible.

References

- Br Med J. 1930;2(3645):817-819.

- Anaesthesia. 1984;39(11):1105-1111.

- Anesth Analg. 2016;122:1101-1107.

- Anaesth Intensive Care. 2015;43(suppl):4-11.

- Anesth Analg. 2009;109(5):1560-1565.

- Open Anesthesiol J. 2017;11:48-67.

Please log in to post a comment

As someone who trained in the horse and buggy days, I try to pass on to residents, students, and CRNAs that “make your first attempt you best attempt”. I can almost always tell the number of years in practice by the preparation. Some of the “ramp” building is a thing of beauty. I am also a big proponent of teaching and performing the “awake fiberoptic intubation”, as it does not “burn any bridges” and has a high success rate. I am constantly imploring my young charges to “look at the patient first, not the monitor”

I also trained in the "horse and buggy era", without the benefit of fiberoptic scopes of any type, pulse oximeters, or ETCO2 monitors (I have never failed to intubate anyone). I was taught there was NOT ANYONE who could not be intubated, ie. we had a hundred different blades to use, etc. Preparing for the best first attempt (as noted in a prior comment) is the key. When someone had a difficult intubation in the past, my first question is "where did it happen? - almost always a University Training center. At that point I know for sure that it was not a "true difficult intubation" but a training situation.

If I am really concerned, I have the patient the patient "breathe" themselves down, insert an LMA (not available when I trained). If I can ventilate the p[atient, I proceed with intubation by whatever means I feel appropriate. If the patient can ventilate on their own or be ventilated "externally" that is the key.

Excellent comments by both previous providers. Seems like the "old" dogs have tricks up their sleeves that most newly trained anesthesia providers just not have had the breadth of experience to work through. I too am old school, having trained in the mid 80's. Only want to add that even though video laryngoscopes have made our lives easier, and much more convenient, they are not the panacea.

1. Proper wedge building is an art form

2. As stated, make your first attempt your best. Don't go down the rabbit hole of "almost saw it, and will get it if I try again with a different blade", etc.

3. Know your next step if plan A fails BEFORE it does

4. Ability to ventilate, whether controlled, or spontaneous, buys you all the time to change your plan.

5. KNOW how to do fiberoptics before you are forced to do it. NEVER just expect to be able to do it as a last resort technique when everyone in the room is panicking. In other words, DO IT regularly and often. I do a lot of complex spine cases, where airways often are challenges, and I regularly do "fiberoptic days". My staff knows what I need, what I do, and how to help me, and they are relaxed because they know it isn't meant as a last minute Hail Mary bailout.

I’m confused, the patient had a normal thyroid-mental distance during her airway evaluation but you mentioned that during intubation she had an anterior larynx. How is that possible?

Yes, that was exactly the case. I think that is why the difficulty of intubation was such a surprise in the first two instances. But in my experience (and here I agree with the comment below from californiadreamin), there are patients with a very small thyromental distance who are easy to intubate and patients with a normal-appearing chin, like the patient in our case report, who are not. There truly is not an exact correlation. At best, a normal thyromental distance can be regarded as a reassuring sign but it is by no means a guarantee.

Why does the thyroid-mental distance indicate anything except to provide liability protection after the fact? My understanding of the literature is that there are no true measurements externally (outside the mouth during an intubation attempt) which indicate what is going on internally (inside the mouth). Trick is to make sure you can ventilate a patient before you back yourself into a corner you cannot get out of.

Just to amplify and add my voice to the prior comments... I don't understand a repeated attempt to ventilate by mask when such has been difficult in the past. Why not go straight to an LMA? If I can't ventilate with a face mask, that's what I'll do anyway, so why waste precious apnea time? Furthermore, my hands are tied up when face mask ventilating. Goal in that case is to continue the anesthetic, ventilating the patient with volatile agent using pressure cycled ventilation leaving me with free hands and plenty of time to ponder "what next"?

Recently I had the challenge of a known difficult intubation where the patient's prior trip to the operating room for a rotator cuff repair resulted in a soft palate perforation after a failed, hurried intubation attempt by a CRNA with a glidescope. Incrediby, the patient returned for a repeat attempt after the surgeon cancelled his case. I insisted on performing the airway management myself. The patient was a very difficult ventilation by mask on the prior attempt, so I placed an LMA after propofol induction. After easy ventilation via the LMA, we relaxed him with rocuronium. and commenced pressure cycled ventilation with sevo/O2. A first laryngoscopy with an angulated glidescope yielded a grade 2a view of vocal cords, but intubation failed because the endotracheal tube bounced off the vocal cords and went perpendicular with attempted advancement. We returned to LMA ventilation while we pondered our next steps. A second attempt with the glidescope using a bougie failed because the bougie kept going posterior to the cords and external cricoid pressure couldn't bring the cords in line. After a third bout of LMA ventilation, the patient was successfully intubated with a bullard laryngoscope using the multifunctional stylet (coaxial tube advancement after airway exchange catheter was place through the vocal cords using the multifunctional stylet).

The point to this rather long comment is in this case, the LMA proved an extremely useful bridge airway in a lesiurely, thoughtful approach to a difficult intubation in a patient where a prior panicked approach had resulted in airway trauma.

Just wondering, why repeated attempts were made by the glide-scope! Were there NO fiberoptic to use through the LMA. Why the regular VL (without the hyper angulation) was not tried FIRST to see if it yields a reasonable view (1 or 2) before using the hyper angulated blade.

Thank you Dr Silbert for a great article high-lighting the importance of positioning,

I worked for almost 10 years at a private Swedish Bariatric Center where we usually did 20-25 elective bariatric cases/week with BMI ranging between 35 and 60. We also took care of complications and acute re-operations. For the first 3-4 years or so we didn't have our own VL or fiberoptic but could, if need be, use one from the public Anaesthetic department adjacent to our own OR. We did roughly 2 500- 3000 cases before the private center acquired its own dedicated C-Mac VL.

During the time before that I borrowed the public departments VL only once and my colleague once too during those 3-4 years. What we did though was a very careful positioning with wedges or pillows to get the patient in an optimal sniffing position and always 30 degree head up. I can't remember any patient that couldn't be ventilated at all with facemask prior to intubation., sometimes slight-moderately difficult but not impossible. I am fully aware that the incidence of a true "can't ventilate, can't intubate" situation might be 0,2 - 2/10 000 cases, so we could have been a bit "lucky".

Interestingly though, after we got our own VL and used it routinely, the positioning routine got less rigorous, though still 30 degrees head-up. This also partly due to the surgeons not being too happy with a wedge. This sometimes resulted in less than optimal view.